Two Countries, One System

On 1 July 1997, Chris Patten, the last Governor of Hong Kong handed the keys of the British colonial-administered territories to Chinese President Jiang Zemin and in one fell swoop, sovereignty was peacefully transferred from the British Crown to the Chinese state.

Hong Kong, Kowloon, and various interconnected island territories had been commandeered by Queen Victoria as the spoils of victory in the Opium Wars. The huge New Territories area had been added in 1898 and leased for 99 years. In a ceremony attended by Tony Blair and Prince Charles, Britain’s lease was up and by default Britain’s rule of Hong Kong and its many adjoining administrative regions had to be handed back.

The UK was clearly concerned that China would rush in and undo the investment that Britain had built up over the years; the economic and social capital that had helped Hong Kong grow into a dynamic, English-speaking, outward-facing, trading nation and financial hub. Remember, China was still a bit player in world affairs at that time and this was just eight years on from the brutal repression at Tiananmen Square. But China was making all the right noises and the Communist Party seemed to be only too delighted to let Hong Kong be its window on the world.

At handover, President Jiang announced: “I wish to extend cordial greetings and best wishes to more than six million Hong Kong compatriots who have now returned to the embrace of the motherland”. He promised “a high degree of autonomy and keeping Hong Kong’s previous socio-economic system and way of life of Hong Kong unchanged and its previous laws basically unchanged”.

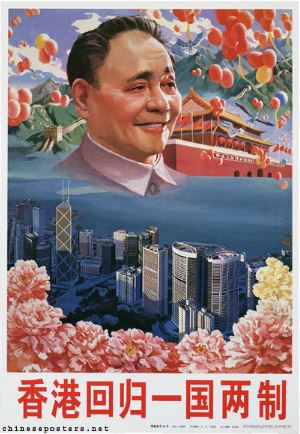

The Chinese mainland would maintain its Socialist rule by the Communist Party of China, while Hong Kong’s notionally autonomous administration would be allowed to continue on its capitalist road. A liberal state with protected rights, but firmly situated within China’s sovereign territorial mandate. This was the essence of Deng Xiaoping’s mantra: “One Country, Two Systems”.

The Chinese mainland would maintain its Socialist rule by the Communist Party of China, while Hong Kong’s notionally autonomous administration would be allowed to continue on its capitalist road. A liberal state with protected rights, but firmly situated within China’s sovereign territorial mandate. This was the essence of Deng Xiaoping’s mantra: “One Country, Two Systems”.

The One Country, Two Systems mantra seemed to represent an untenable contradiction, and it was this questionable balance of power that Britain was afraid of losing out to. In its last gasp efforts to maintain democratic norms in Hong Kong, the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 (signed by Margaret Thatcher) allowed for the retention of free speech, free assembly, and introduced elected representation, insisting that this situation should pertain unchanged for 50 years after handover. That is, until 2047 when Hong Kong would be fully integrated back into the Chinese embrace. This formed the basis of the so-called Basic Law, the constitutional framework operating within Hong Kong.

Now there only 26 years left to run. But before the ink was dry on the settlement, China was contesting Britain’s desire to have a role in Hong Kong affairs. China’s deputy ambassador to Britain, Ni Jian declared that the agreement “only covered the period from the signing in 1984 until the handover in 1997”. Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying emphasised that “Britain has no sovereignty over Hong Kong that has returned to China, no authority and no right to oversight…The real aim of a small minority of British people trying to use so-called moral responsibility to obscure the facts is to interfere in China’s internal affairs.

Under the Basic Law, the territory is governed by a Legislative Council (Legco) comprising 75 representatives – 50% of whom are elected by popular mandate. This was Britain’s cynical parting shot, replacing its colonial administration with a manufactured democratic one – something that it hadn’t been particularly concerned about before. It was primarily to scupper Chinese influence.

The legislature as currently constituted comprises business interest groups – from professional constituencies and pro-Beijing lawmakers. The head of the Legco, chief executive Ms Carrie Lam is a direct appointee of the Chinese state (paid, incidentally US$500,000 per annum – which we are led to believe is 20 times the salary of Xi Jinping, and twice the salary of Donald Trump). Furthermore, even though there is an independent judiciary which includes non-permanent judges from other common law jurisdictions who sit on the Court of Final Appeal (Lord Sumption is the current UK appointee, for example), the final ruling on the Basic Law lies with the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of China. Article 1 of the Basic Law declares that Hong Kong is part of the People’s Republic of China… albeit with Western characteristics.

Unsurprisingly as the clock ticks down to eventual full integration, China is increasingly laying down the law – literally – while Hong Kongers fight to retain their distinct identity. Hong Kong is officially part of China but over the last 15 years, the number of 18-29-year-old Hong Kong residents identifying as Chinese, has shrunk from 28% to virtually zero. Those identifying as Hong Kongers has risen from 40% to 72% in the same period.

The growth of the Shenzhen mega-city across the water, and the sense that Hong Kong is being threatened by its far bigger partner, adds to the sense of uncertainty. It has created something of a siege mentality. With perfect timing, the coronavirus lockdown has appeared as a metaphor for life under an alien regime. Job opportunities for graduates are scarce and poorly paid, while housing is on average 21 times median income.

In response, some small sections of Hong Kong society have expressed their longing for different models of society. These fall into four camps. There are those who have a nostalgia for the colonial security of British rule; others look to America as the only power able to force China to back down and back off; while others wish to go back the security blanket of One Country, Two Systems in the hope that China will continue to invest in land reclamation, jobs and real estate development. The fourth camp, and by far the most appealing to young Hong Kongers are those fighting for freedom. An intangible desire for autonomy, a desperation to maintain democratic traditions, and a fight to prevent the encroachment of authoritarianism.

Many in the younger generation seek peaceful civil disobedience, while the older generation tend to be concerned at the collapse of deference and the breakdown of law and order and want the authorities to intervene. A generational and cultural rift is growing. Into the mix are those fighting for the creation of a new cultural identity – as yet unspecified – and others expressing uncomfortably anti-Chinese hostility. Most of these responses reflect a sense of desperation and fractiousness rather than a conscious plan. Indeed, most of the protests up to now have refrained from calling for full independence from the Chinese Communist Party-run mainland.

Demands for a truly independent Hong Kong have for a long time been a minority interest, even among activists. But after serious violations of the spirit of the Basic Law over the last 20 years (including illicit removals of Hong Kong dissidents to the mainland), recent infractions have spilled over into the most serious social unrest since British hand-over. Predictions are futile.

The attempt to introduce an Extradition Bill (to give snatch squads the cover of legality) resulted in 2019’s year-long protests. But it is the latest National Security Bill – passed in May at the Party conference in Beijing – that has reignited protests. The legislation permits the Chinese Communist Party to ban criticism of Beijing’s actions and that “when needed, relevant national security organs of the Central People’s Government will set up agencies in Hong Kong to fulfil relevant duties to safeguard national security in accordance with the law”. Who needs cross-border snatch squads when you have a legal presence over the border?

In some respects, the National Security Bill is the culmination of all previous efforts by China to implement direct rule and to oversee Hong Kong affairs. This time it is claimed to be in the interest of fighting sedition, terrorism, subversion, and any act that “undermines the power or authority of the central government”.

China has several reasons to up the ante. Firstly, with the easing of coronavirus, many more people are emerging from lockdown to continue last year’s unfinished struggle and China wants to act swiftly. Secondly, Hong Kong’s Legco elections will take place in September and China has already started to arrest and detain pro-democracy activists in a pre-emptive strike against organised disruption. Finally, the end of 2020 marks the date when President Xi Jinping pledged that China would be a “moderately prosperous society”.

The year 2021 was chosen to commemorate the centenary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party and nothing should deflect China from this economic target. With GDP slumping to -6.8% in February, the economic reality could be humiliating, and President Xi does not need any embarrassing protests to add to his woes. The Party will definitely not sit by and watch protestors undermine a desperately needed Hong Kong economic recovery, nor will it want to permit the free expression of anti-Chinese protests to be broadcast around the world.

By undermining the very essence Hong Kong’s unique democratic status China risks creating a national independence movement. Up until now, protests have stopped short of demanding Hong Kong national sovereignty. More importantly, if this continues, Western states may be dragged into a culture war that will have significant ramifications for global trade and geo-political influence in the region.