Olympic Meddles

In the run-up to the Beijing Winter Olympics there emerged a coordinated campaign to get the event renamed “The Genocide Games.”

In a recent debate coordinated by Human Right Watch, Tibetan and Uyghur activists called for international solidarity in opposition to China hosting the Winter Games. Emotional testimony from Uyghur Muslims and other religious and ethnic minority groups within China subsequently featured in newspaper headlines across the globe, as the international spotlight begins to focus on the Olympic Games. Hong Kong civil rights activists, Taiwanese nationalists and Falun Gong religious protestors amongst others weighed in on the campaign to put pressure on the Chinese state. The bandwagon against the Communist Party’s mistreatment of Uyghurs took on a wider significance at a time when the whole world is watching.

A number of countries have said that they will not attend the Olympics but are citing Covid as a convenient excuse in order to not offend the Chinese hosts. The US, UK and Australia are more explicit and have already agreed not to send diplomats to Beijing 2022, citing “genocide and crimes against humanity” in Xinjiang as the reason. Republican Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas has demanded that the United States “fully boycott the genocide Games in Beijing.” American ice skater, Timothy LeDuc — the first openly non-binary person to compete at a Winter Games – has condemned China’s “horrifying” human rights abuses, while Canada’s champion snowboarder Drew Neilson, now retired, says that a boycott is the “morally correct thing to do”.

International concern is growing at the reported “unconscionable crimes against humanity” suffered by the Uyghur peoples in particular. The Daily Mail sums up the situation “How Beijing’s 2022 Winter Olympics ‘sportswashing’ propaganda mirrors Hitler’s 1936 efforts in Berlin.” If indeed, attending the Winter Games is the equivalent of performing a Nazi salute at a Leni Riefenstahl film festival as millions are sent to extermination camps, then presumably there ought to be more than muted concern.

China’s one-party authoritarian power structure has been well known for decades. It was exactly 50 years ago that Nixon’s entered détente talks with Chairman Mao, right in the middle of the Cultural Revolution where tens of thousands of so-called subversives, minor criminals and counterrevolutionaries were being executed without the West batting an eyelid. That was a mere ten years after the Great Leap Forward where around “45 million Chinese people were worked, starved or beaten to death.” The West was there to find “common ground, despite our differences”. It seems that, in international relations, moral dilemmas are relative.

So, what do we really know about the situation today?

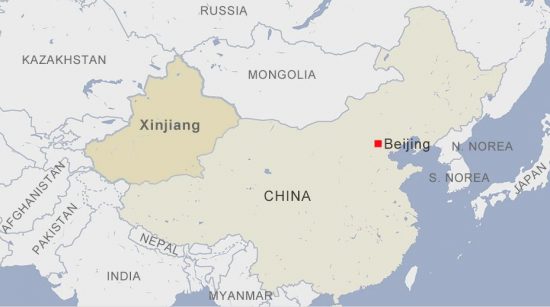

Uyghurs are a Turkic people originating in Xinjiang [New Frontier] the vast region of China – covering over 50 per cent of Northwest China. It is a key conduit for the Belt and Road trade route from China to Asia and beyond. The province borders eight countries including Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and even a 75km border with Afghanistan. Indeed, since the withdrawal of Western forces from Afghanistan last year, the Taliban have been working with the Chinese state to expel militant Uyghurs – allegedly represented by the Turkestan Islamic Party who are fighting for an independent Turkestan. China is logically concerned that domestic jihadis might destabilise the region but marginalising an entire community has become a grotesque abuse of power. It is not unlike the situation in Western countries where threats of ISIS attacks have encouraged the use of anti-terrorism measures as a catch-all excuse for restricting rights across the board.

Uyghurs are a Turkic people originating in Xinjiang [New Frontier] the vast region of China – covering over 50 per cent of Northwest China. It is a key conduit for the Belt and Road trade route from China to Asia and beyond. The province borders eight countries including Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and even a 75km border with Afghanistan. Indeed, since the withdrawal of Western forces from Afghanistan last year, the Taliban have been working with the Chinese state to expel militant Uyghurs – allegedly represented by the Turkestan Islamic Party who are fighting for an independent Turkestan. China is logically concerned that domestic jihadis might destabilise the region but marginalising an entire community has become a grotesque abuse of power. It is not unlike the situation in Western countries where threats of ISIS attacks have encouraged the use of anti-terrorism measures as a catch-all excuse for restricting rights across the board.

While some reports suggest that around 5,000 Uyghur militants are fighting in Syria, jihadism remains a minority interest amongst Uyghurs (in the same way that it is a minority interest amongst all racial, religious and national populations). While China routinely rounds up the usual suspects, the vast majority of Uyghurs are innocent, law-abiding, non-militant, Sunni/Sufi Muslims who are simply caught up in the blanket crusade to eradicate a cultural and economic threat – as the Chinese leadership sees it – to the continued existence of the state.

The ruling Party has watched with trepidation the conflicts in the Arab world over the last 20 years, in the full knowledge that militant separatists are within and around their own borders. The traumatic events of 9/11 and the subsequent Western war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan – in which, incidentally, many hundreds of Uyghurs were bombed and captured by US forces in their 20-year conflict in the country – greatly influenced the Chinese Communist Party’s view of some Uyghurs as a potential threat. This over-statement has led to their dehumanisation and the brutal incarceration of those deemed to be a threat. Simply by being a Uyghur is cause for suspicion as far as the authorities are concerned and they list a range of caricatures as early warning signs of Uyghur radicalisation. In many regions of Xinjiang, China has banned long beards, wearing the veil or meeting with people who are “too religious”. Given that a large proportion of Sufi Uyghurs are actually moderate, do not wear the veil, enjoy a drink, and do not repress women’s roles in society, China is engaging in dodgy parody policing. In some ways, it is the opposite of the reaction of UK authorities who seem fearful of pointing the finger at Islamist groups for fear of being accused of labelling ordinary decent Muslim communities as a problem.

The ruling Party has watched with trepidation the conflicts in the Arab world over the last 20 years, in the full knowledge that militant separatists are within and around their own borders. The traumatic events of 9/11 and the subsequent Western war on terror in Iraq and Afghanistan – in which, incidentally, many hundreds of Uyghurs were bombed and captured by US forces in their 20-year conflict in the country – greatly influenced the Chinese Communist Party’s view of some Uyghurs as a potential threat. This over-statement has led to their dehumanisation and the brutal incarceration of those deemed to be a threat. Simply by being a Uyghur is cause for suspicion as far as the authorities are concerned and they list a range of caricatures as early warning signs of Uyghur radicalisation. In many regions of Xinjiang, China has banned long beards, wearing the veil or meeting with people who are “too religious”. Given that a large proportion of Sufi Uyghurs are actually moderate, do not wear the veil, enjoy a drink, and do not repress women’s roles in society, China is engaging in dodgy parody policing. In some ways, it is the opposite of the reaction of UK authorities who seem fearful of pointing the finger at Islamist groups for fear of being accused of labelling ordinary decent Muslim communities as a problem.

It might be over-generous to excuse China’s brutal treatment of minorities by saying that it is “incompetent” at foreign affairs and none too good at domestic politics either. But given that the country was isolated from the world until 1976 and is still considered to be an underdeveloped country (using World Bank and United Nations’ criteria), it is certainly unskilled in many areas of international relations and conventional diplomacy. That said, there is no disguising the fact that it is well-practised at being an authoritarian state that brooks no challenge to its internal stability.

Since the American retreat from Afghanistan, China has cultivated the Taliban in the hope that they will arrest or deport their domestic Uyghur militants to quell the problem at source. However, ISIS cells in Afghanistan and elsewhere are picking up the pieces and recruiting many angry, embattled and dispossessed Uyghurs to the fight for freedom, who are possibly using the misguided framework of an Islamic caliphate as the means to an end.

But the exaggeration exists on both sides. The recent Uyghur Tribunal hosted in London in 2021 concluded that there was “no evidence of mass killings” in Xinjiang, but that “the alleged efforts to prevent births amounted to genocidal intent.” Whatever you think of this description of genocide [which admittedly chimes with Article II of the UN Genocide Convention], Nazi extermination camps is surely not a legitimately comparable image. Of course, there is justifiable revulsion at the grotesque policy of forced sterilisations of Kazakh and Uyghur women to reduce their population, but putting this in perspective, for the last 40 years, Uyghurs and other minorities were, in principle, exempted from China’s one-child policy. For 35 years, it was the majority, urban, Han population that were being sterilised, forced to abort, or penalised for having more than one child. This ruthless strategy raised few eyebrows in the West since its implementation in 1978 – only ending in July 2015 – having prevented approximately 400 million births. Welcome to China.

Meanwhile, the Uyghur population has allegedly doubled in the last 40 years but is still a minority within its own territory [and its population growth rates has massively declined under the influence of the one-child policy since 2015]. As an aside – and not wishing to trivialise the situation in China – many Western environmentalists have long argued for a one or two child policy as a solution to economic and environmental problems, as Harry and Megan have done recently. Indeed, UK academic Dr Guillebaud noted that “compulsory limits on births may become unavoidable” in the west. In general, it seems that there is justifiable horror at the coercive methods used in China, but less so the restrictive population measures posed by environmental advocates elsewhere.

The Nazi-style imagery of the Chinese state is further emphasised by reports of concentration camps, internment camps, re-education centres in which Uyghurs, Kazakhs and other minorities are held. Anti-fascism plays well in the west and various news outlets have asserted that there are one, two or even three million people incarcerated in these prisons. There is reasonable and growing evidence to suggest that these places exist and that many Uyghurs are held against their will. But most of the “evidence” is speculative because China is adept at blocking information and stopping journalists from reporting the facts, especially if those facts put the Party in a bad light.

However, when a Pulitzer Prize is given to a team of writers for their speculative interpretation of events on the ground, then questions need to be asked – more about the status of journalism, criticism, and evidence-gathering than maybe the situation of which they speak. BuzzFeed News won the award for a series of “innovative articles that used satellite images, 3D architectural models, and daring in-person interviews”.

Having noticed that a number of buildings were being rapidly built in the deserts of Xinjiang, the investigators compared NASA, Google, and Baidu images to assess what these facilities might be used for. With an architect on board, they examined the layouts of the structures to resolve that these were most likely detention facilities: assessed them in line with Chinese prison building regulations, estimated the likely internal spatial arrangements and calculated the potential capacity of inmates. Buzzfeed were careful to say that 1.1 million people could be held, but this has become the accepted figure. Their report claims that “a total of more than a million Muslims have been detained or imprisoned over the last five years” adding, “with an unknown number released during that time.”

The research was checked against the testimonies of 28 ex-inmates’ who, it admits, “were released too long ago to have spent any time in one of the brand-new facilities.” Out of those 268 new facilities, “176 facilities have been established by satellite imagery alone”. This somewhat circumstantial evidence has apparently enabled the researchers to assert the religious or national persuasion of the inmates and to record extrajudicial treatment meted out. For this, BuzzFeed et al was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting.

Brave investigative journalism is essential for our understanding of what is happening in China. Unfortunately, factual accuracy can be drowned out by emotionally attached storylines, and this can lead to a disdain for facts that do not fit the narrative. As an example, as we go to press, Canada is reporting the discovery of hundreds of bodies of Indigenous children, killed, and disposed of in the grounds of various Catholic schools since 1900. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has apologised for the scandal and has asked the pope to do the same. This national scandal is based on “the evidence of remains” but not remains per se, simply radar readings of the area that seem to indicate that this could potentially be graves of unknown persons. Curiously, the outpouring of guilt and shame, blame and retribution, seems to be more compelling than digging up the area to find if the story is borne out by the facts.

Healthy scepticism does not diminish the search for truth. The desire to oppose the brutal reality for many Uyghurs in Xinjiang and around China should not cloud our judgement. How we react to these troubling situations must surely be based on reason rather than modelling. Talk of boycotts, trade embargos, financial penalties, and other diplomatic power plays is a dangerous heightening of tensions against a sovereign state on the basis of algorithmic evidence; albeit anyone who has been to China will fully acknowledge that certain minority groups are having their rights fundamentally abused. But then again, for twenty years China has anxiously observed the west’s mounting “war on terror” on the other side of its borders, the detention of Uyghurs in Guantanamo, and probably didn’t think they’d be criticised.

Healthy scepticism does not diminish the search for truth. The desire to oppose the brutal reality for many Uyghurs in Xinjiang and around China should not cloud our judgement. How we react to these troubling situations must surely be based on reason rather than modelling. Talk of boycotts, trade embargos, financial penalties, and other diplomatic power plays is a dangerous heightening of tensions against a sovereign state on the basis of algorithmic evidence; albeit anyone who has been to China will fully acknowledge that certain minority groups are having their rights fundamentally abused. But then again, for twenty years China has anxiously observed the west’s mounting “war on terror” on the other side of its borders, the detention of Uyghurs in Guantanamo, and probably didn’t think they’d be criticised.

__________________________

Austin Williams [@Future_Cities] is the director of the Future Cities Project.