McC-arch-yism

By Austin Williams | 16 March 2013

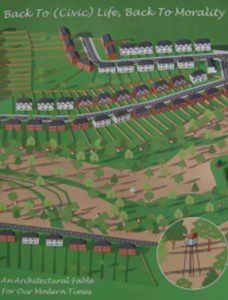

In her book, “Back To (Civic) Life, Back To Morality: An Architectural Fable For Our Modern Times”, Elly Ward proposes – somewhat caustically – that a series of ‘moral rehabilitation” centres be built around the UK that are “open to anyone lacking in moral values and showing signs of civic disengagement.” Satire works when it mirrors reality and indeed, we are living in a period where the notion of nudging people into officially sanctioned “good” behaviour is an unquestioned orthodoxy.

As David Hockney writes in The Guardian: “We live in a very shallow age” when mainstream moral intervention is seen as radical; moreso when this radicalism becomes professionalised. (That’s a contradiction in terms, surely?).

As David Hockney writes in The Guardian: “We live in a very shallow age” when mainstream moral intervention is seen as radical; moreso when this radicalism becomes professionalised. (That’s a contradiction in terms, surely?).

Currently, the ethics tsars are at work in America arguing that architects be not engaged in the construction of prison facilities that torture or execute. Good idea, you might think, except that it ignores the fact that many people believe in constructing such places. Obviously, some people think that they are good ideas otherwise they wouldn’t be being built in the first place, and undoubtedly some architects are amongst them. In other words, whether the morally pure “designerly community” like it or not, some architects think that convicted felons deserve the severest form of punishment and are prepared to build those internment facilities. I am reasonably sure that some architects – unlike myself – believe in the death penalty and are prepared to assist in some way. While there ought to be a debate about the moral value of state torture and execution per se, why should there be some kind of moral consensus that this is an unprofessional conviction?

For example, as a young architectural assistant working for Ryders in Newcastle (or Ryder Nicklin as it was then), I was employed on various projects, from Blyth Police Station (admittedly it’s not San Quentin, but it was still not a nice place to be on a Saturday night) to Vickers tank factory. No questions asked. We don’t all get commissioned to build orphanages and hospitals.

However, in their petition to the American Institute of Architects, the morally untouchable, Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) states that: “architects should not participate in the design of spaces that violate human life and dignity”. High-minded guff. This is just a cowardly way of challenging the state’s use of violence, by threatening those who join in. Being morally blackballed for accepting, what others deem to be an unethical commission, is a slippery slope. What next for those who accept commissions in Syria, China, Sudan or other countries of which we know little, but fear the worst?

Furthermore, architects who accept commissions from morally repugnant clients should not be tarred with the same brush. In many instances, we don’t know – nor should we know – the political intent behind our clients brief. However, if an individual architect wishes to withdraw his or her services, due to personal or political disagreements with a project’s particulars, then that is up to him or her. But to be threatened with professional ostracism for having allied oneself to a person deemed to have reprehensible views should cause many architects to quake.

The irony is that the (illiberal) liberals who oppose the construction of hard-line correctional institutions are actually proposing an ethical straight-jacket for professionals. It is they who are constructing correctional behaviour units that genuinely violate the essence of human life and dignity: free choice, autonomy and personal and political conviction.

However reprehensible or repugnant the function of particular buildings, we must argue for the freedom of choice and expression of those who design them. Indeed, architects who hold the conviction that violent retribution against criminals is legitimate are, in my mind, politically wrong, but they are not necessarily lesser architects. Physical torture and state repression is not a design issue.

Instead, we have a duty to oppose the bullying by quasi-autonomous organisations like ADPSR who are trying to designate what we should consider to be a morally acceptable professional commission. This is the thin end of the wedge. Don’t sign the petition.

Austin Williams is director of the Future Cities Project