by Austin Williams

by Austin Williams

China launched its social credit system at its party conference in 2014 at the 18th Party Congress with the aim of “strengthening sincerity in government affairs”. A little bit more sincerity in UK politics might not go amiss, you might think, and indeed, the Chinese policy document examines mechanisms to “improve government credibility and establish an honest image of an open, fair and clean government”. Since then it has proceeded – in its usual technocratic manner – to develop a total monitoring system to ensure that its “good behaviour” model is rolled out across society. There is no escape.

The initial Party Directive centres around the need to “build a harmonious Socialist market economy”. It aims to do this through a relentless armoury of rewards and punishments to ensure that good behaviour is feted and anti-social behaviour eradicated. As they say: “Keeping trust is glorious and breaking trust is disgraceful.” Sold as a patriotic system on honour, the social credit system affects every corner of Chinese society. It gives marks – credits – to individuals who engage in socially worthy activities; and black marks to those indulging in dishonest, nefarious, illegal or simply anti-social activities. The intention is to “raise the entire society’s sense of sincerity”. It is currently being piloted and will be rolled out across the country by 2020.

From annoying passengers who sit in the wrong train seat and refuse to move, to walking your dog without a lead, to arguing at an airline check-in desk; each one of these will be targeted with a lower social credit score resulting in, respectively, not being allowed to travel, having your dog taken away, or being banned from flying. This is the state stepping in as the arbiter of last resort to resolve disputes at a local level. It will also punish fraudsters, bad parents and dodgy party officials by removing the right to send their children to good schools or removing the opportunity for promotion.

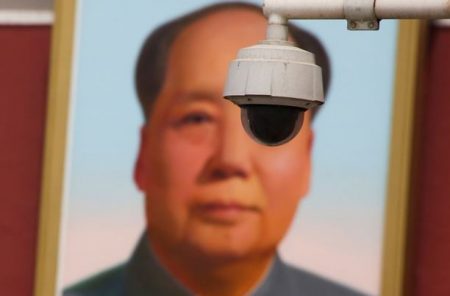

A low credit rating can do serious harm, not only to your career but also your family’s life chances and it is all made possible by state monitoring cameras, intelligence records, data-mining and other forms of surveillance that ensures that justice is swift. Travelling in a car in Jiangsu Province recently, the driver ran a red light and immediately received a message on his phone telling him that the fine had been deducted from his bank account.

While the west expresses outrage of at this extension of state power against its citizens – and rightly so – there are three things that need to be borne in mind. First of all, this is China, what do you expect?

The Guardian points out that this new social credit system is “an Orwellian tool of social monitoring”. No shit, Sherlock. What part of “China is a single-party state” don’t you get? Actually, it is more shocking arriving in Heathrow airport to finger-printing, retina and body-scanning and biometric passport checks precisely because we seem to have given up a proud history of civil liberties campaigning and ID card protests. Arriving in Shanghai to super-fast fingerprint and facial recognition technology seems about standard for anyone who has read a little Chinese history.

The Guardian points out that this new social credit system is “an Orwellian tool of social monitoring”. No shit, Sherlock. What part of “China is a single-party state” don’t you get? Actually, it is more shocking arriving in Heathrow airport to finger-printing, retina and body-scanning and biometric passport checks precisely because we seem to have given up a proud history of civil liberties campaigning and ID card protests. Arriving in Shanghai to super-fast fingerprint and facial recognition technology seems about standard for anyone who has read a little Chinese history.

For 70 years, China has monitored society’s actions, it’s just that now it is considerably more technically proficient in doing so. In the past, China’s parochial peasant social relations made it easy to mark a person out as a troublemaker and administer punishment. In today’s social credit rating system it’s a damn sight easier to do. Since 1958, for example, China has used an internal passport system that prevents people living in certain parts of China, monitoring their movements, denying them rights and opportunities and requiring an army of officials, stamps, checks and procedures to do so. Now it can appear to liberalise that process, taking it out of the visible spectrum and making surveillance less noticeable. You will still be denied travel documents, banned from trains, refused healthcare, etc but it’ll be adminstered by the cloud rather than the crowd. That distance means that it’s more difficult to argue your innocence.

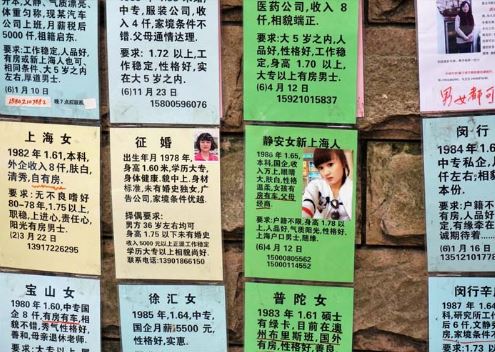

It’s insidious, but Chinese people are circumspect precisely because they are used to it. Every weekend across China, parents of unmarried adults sit in Marriage Markets in public parks with advertising signs, promoting their children’s qualities (age, height, weight, hobbies, job prospects) to ensure a good match. That is the traditional way, they say. Nowadays, the social credit system gives parents the opportunity to garner clear advice about the credit rating of the “wrong” kind of person. Avoid a lazy, feckless or profligate marriage suitor – clearly defined by his/her inability to get a mortgage – to avoid the rest of the family being tarnished by association.

It’s insidious, but Chinese people are circumspect precisely because they are used to it. Every weekend across China, parents of unmarried adults sit in Marriage Markets in public parks with advertising signs, promoting their children’s qualities (age, height, weight, hobbies, job prospects) to ensure a good match. That is the traditional way, they say. Nowadays, the social credit system gives parents the opportunity to garner clear advice about the credit rating of the “wrong” kind of person. Avoid a lazy, feckless or profligate marriage suitor – clearly defined by his/her inability to get a mortgage – to avoid the rest of the family being tarnished by association.

The second rationale (not that I am endorsing it in any way) is the fact that China needs to re-invent social cohesion. With the collapse of communism, there is no ideological framework governing Chinese society these days and the Party is relying increasingly on economic measures – personal wealth and financial satisfaction – to maintain stability. Threats to that system, which are ultimately threats to the Party and the maintenance of the state, must not be allowed. So economic opportunities come with an unhealthy does of threats. Evaluating “mass activities for moral judgement” through the social credit system is an efficient way of running a country that sees its citizens as mere statistics.

Information gathering is made simple by online tools like Weixin (also known as Wechat, the equivalent of WhatsApp) run by Pony Ma and Amazon-equivalent Alibaba run by Jack Ma (no relation). These all-seeing apps makes Cambridge Analytica look like a bunch of amateurs. Wechat, for example, is a party affiliated company with one billion monthly users. It’s an all-in-one app that allow you to order taxis, send messages, pay utility bills, update bank records, and access your digital ID card. Its payment function has almost made cash obsolete – hence the emergent power of credit. In this way, the government can liberate spending power but also rein in problematic behaviour at the click of a switch. Whereas, people were often beaten or incarcerated for speaking ill of the party, today, you might be refused a loan to buy a car. It all seems so much more civilised. And to be seen as civilised is a hugely important goal for China, a country desperate to enter onto the world’s stage.

Information gathering is made simple by online tools like Weixin (also known as Wechat, the equivalent of WhatsApp) run by Pony Ma and Amazon-equivalent Alibaba run by Jack Ma (no relation). These all-seeing apps makes Cambridge Analytica look like a bunch of amateurs. Wechat, for example, is a party affiliated company with one billion monthly users. It’s an all-in-one app that allow you to order taxis, send messages, pay utility bills, update bank records, and access your digital ID card. Its payment function has almost made cash obsolete – hence the emergent power of credit. In this way, the government can liberate spending power but also rein in problematic behaviour at the click of a switch. Whereas, people were often beaten or incarcerated for speaking ill of the party, today, you might be refused a loan to buy a car. It all seems so much more civilised. And to be seen as civilised is a hugely important goal for China, a country desperate to enter onto the world’s stage.

Of course, the growth of state monitoring and information-gathering is alarming, but the technology is not what we should be getting most paranoid about. Through China’s social credit system, we see the ham-fisted and brutal control mechanisms of a developing country, where the government can openly advocate the “building and use of morality classrooms” (possibly legitimising the Uyghur camps in western China).

But my final point is that while condemning China – which is easy – the blasé acceptance of civil liberties incursions in the west is actually more challenging. The Chinese policy documents wax lyrical about “creating a trust-breaking blacklist of tax-breaking corporates” or the “establishment of civil service sincerity dossiers” undoubtedly appealing to the anti-globalisation lobbyists in the west. Credit withdrawal for “poor energy audits” have severe consequences for the individuals concerned but I wouldn’t be surprised to find that there is a sneaky regard in many western circles for China’s tough love.

Speaking of Facebook’s ubiquitous presence in many people’s lives in the UK, The Guardian’s John Harris wrote: “The tyranny of algorithms is part of our lives: soon they could rate everything we do”. True, but when Dominic Grieve MP calls for a government-supported boycott of social media to pressure them into handing over private data, we have an even more insidious incursion into our freedom. It’s important to condemn the abuses of state-power in China, but not if we distract from pointing out a growing contempt for freedom, democracy and civil liberties in this country.

Austin Williams is author, China’s Urban Revolution and director, Future Cities Project.

Twitter: Future_Cities