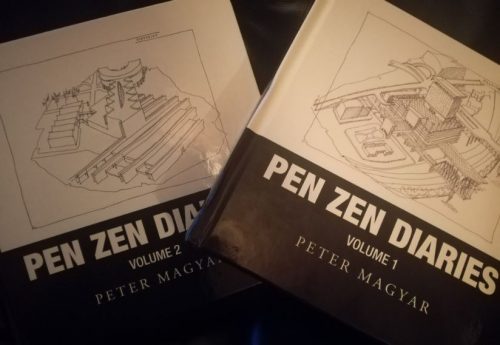

Renowned architect and academic, Dr. Peter Magyar seems currently to be writing one book after another, in double-quick time to illustrate and diseminate his understanding of the intellectual, emotional and intuitive processes of design. With three major tomes re-published in the last 18 months alone, he is clearly reflecting on his illustrious career, seeking to expound upon his research methodology and broadcast his ideas to the world. That said, he has already published more than 20 books and written widely in academic and international journals. This review will deal with the two volumes under the collective title “Pen Zen Diaries”, which clearly signpost his lifelong interest in what he calls “the transformation of spirit to matter”.

Renowned architect and academic, Dr. Peter Magyar seems currently to be writing one book after another, in double-quick time to illustrate and diseminate his understanding of the intellectual, emotional and intuitive processes of design. With three major tomes re-published in the last 18 months alone, he is clearly reflecting on his illustrious career, seeking to expound upon his research methodology and broadcast his ideas to the world. That said, he has already published more than 20 books and written widely in academic and international journals. This review will deal with the two volumes under the collective title “Pen Zen Diaries”, which clearly signpost his lifelong interest in what he calls “the transformation of spirit to matter”.

Originally from Hungary, Peter Magyar settled in the US where he is currently Professor of Architecture (and ex-head) at Kansas State University. In an impressive career, he was the founding director of the School of Architecture at Florida Atlantic University, and also head of the Department of Architecture at The Pennsylvania State University. A century ago, Penn State was the key institution that took Boxer Rebellion scholars from China – like the young Liang Sicheng – to train to be an architect (Sicheng’s own father had campaigned to introduce modern, Western thought to Chinese society). In the newly emerging republic, Liang came to be known as the “father of modern Chinese architecture”. It is a pleasingly circular turn of events that brings Magyar to explore and examine the Chinese philosophical roots to design.

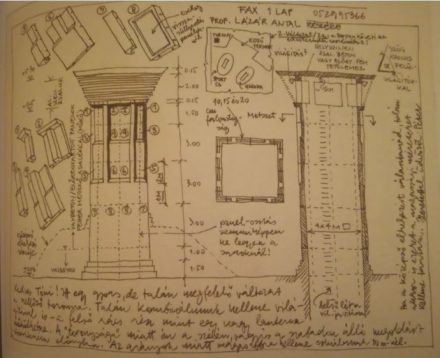

In his books, we sway from Feng Shui to I-Ching, from Yin to Yang, from solid to void, in a fascinating investigation of “traditional Chinese urban principles”: – principles of thinking and doing. Magyar’s books are a treasure trove of drawings, explorations and conceptualisations that focus on his “think-ink” (that means to allow the architect to think, to take risks, to dream, through the process of doodling). “To draw without much thinking is as important as the opposite of it” he says in Volume 1. “Involuntary exaggeration (in sketching) is necessary because it reveals the sub-conscious”. These little motifs – like Confucian soundbites – occur throughout the first part of the book and help us understand the processes being played out.

In his books, we sway from Feng Shui to I-Ching, from Yin to Yang, from solid to void, in a fascinating investigation of “traditional Chinese urban principles”: – principles of thinking and doing. Magyar’s books are a treasure trove of drawings, explorations and conceptualisations that focus on his “think-ink” (that means to allow the architect to think, to take risks, to dream, through the process of doodling). “To draw without much thinking is as important as the opposite of it” he says in Volume 1. “Involuntary exaggeration (in sketching) is necessary because it reveals the sub-conscious”. These little motifs – like Confucian soundbites – occur throughout the first part of the book and help us understand the processes being played out.

It’s a book that comprises hundreds of beautifully simple, well-executed, freehand sketched images. Each drawing, or study, is contained on a square page, with a freehand border and identifying number. Axonometrics, perspectival sketches, worms’-eye projections, plans, sections, details, and more, are lovingly catalogued to demonstrate the progression in thinking – and thinking-processes – involved in the design of a series of actual buildings. It becomes clear, he says, “I am not making the drawings, they are making me”. He continues: “The method of reduction, staple of all kinds of research, provided me insights and discoveries, which with I am able to operatively apply and expand since that time”.

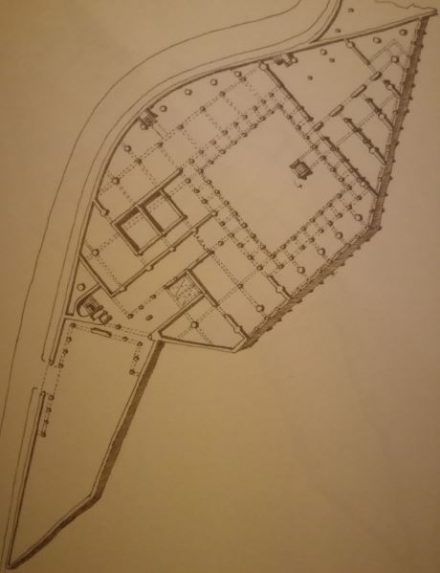

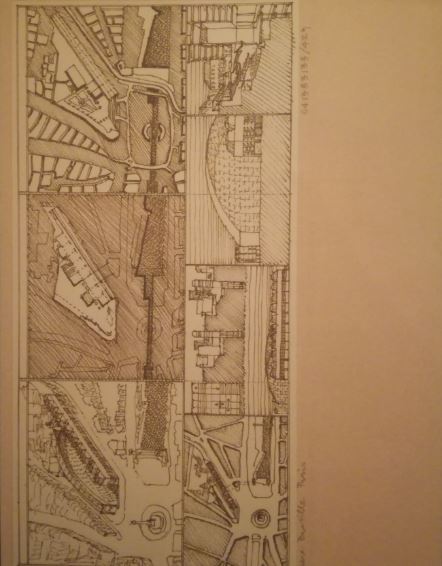

The second section has more delightfully-detailed pencil drawings examining the Hong Kong Peak competition; exploring materiality, axes, topography. It is a study in the “visceral, cerebral and the cosmic dimensions” of building form. The final section of Volume 1– on a Bastille project – contains battle-scared historic drawings of delightful penmanship originating some 40 years ago.

Magyar continues the thesis in Volume 2, “working at the boundaries of the known, the unknown and the unknowable”. Whereas Donald Rumsfeld was once chastised for his phrase: “unknown unknowns”, Magyar is unabashed. “I prioritize the latter two notions”, he says.

The first Chapter Volume 2 is a brilliant example of the evolution of a design. It is almost the storyboard of a film script, as the narrative develops, and is frozen and captured. The chapter is the externalisation of a mind’s eye. The drawing technique and development of a range of ideas is something for students to emulate. Ditto the drawings for the Budapest Sports Hall (Tüskecsarnok, completed in 2012). The final scheme at Yokohama is an attempt at democratically, poetically dealing with a major public project.

The first Chapter Volume 2 is a brilliant example of the evolution of a design. It is almost the storyboard of a film script, as the narrative develops, and is frozen and captured. The chapter is the externalisation of a mind’s eye. The drawing technique and development of a range of ideas is something for students to emulate. Ditto the drawings for the Budapest Sports Hall (Tüskecsarnok, completed in 2012). The final scheme at Yokohama is an attempt at democratically, poetically dealing with a major public project.

At its simplest, this book will teach you to draw and to learn from the process; with either simple line studies, and ink renderings. (It also contains the occasional graphic redolent even of Marvel comics). Architects, he says, “should aspire to reflect and invent the best of the present and weigh its value in the future”. A refreshing thesis, seldom heard in a contemporary discourse that tends nowdays to suggest that we should avoid the so-called “harms” of today lest we create problems tomorrow.

Indeed, he describes Architecture’s design processes as open-ended, which he sees as a good thing. He suggests that the “non-normative status of our discipline has to prevail, since it is the immeasurable aspects of our built environment that elicit wonderment and awe!” For me, these Volumes are a cri-de-coeur for experimentation and the exercise of judgement. For that alone – and these books are much more – Professor Peter Magyar is to be congratulated.