Down and out in Paris and London by George Orwell.

A review, by Shelagh McNerney

Seventy years have now passed since George Orwell died. I have read almost everything he ever wrote; from his early essays, his reviews of Charles Dickens, his Catalan adventures, his observations of domestic life and wartime death, from the 1920’s to 1950’s to the great dystopias “1984” and “Animal Farm”. And his letters.

Seventy years have now passed since George Orwell died. I have read almost everything he ever wrote; from his early essays, his reviews of Charles Dickens, his Catalan adventures, his observations of domestic life and wartime death, from the 1920’s to 1950’s to the great dystopias “1984” and “Animal Farm”. And his letters.

The primary reason for this is because my dad told me to.

My dad was a man born in 1922 into the north Liverpool, Irish, Catholic ghetto and who described himself as a supporter of the Labour Party, a trade unionist, an Evertonian. Clearly a man accustomed to being on the losing side.

For a hundred years my dad’s extended family scurried around the rat-infested streets of north Liverpool, scrubbed clothes, and steps, worked as porters, as tanners. They drowned at sea, died of starvation or disease, in the trenches. They tried again and baptised their children and prayed to God. Then the bombs fell from the sky and finally cleared the slums and decrepit industry and led to the dispersal of this ghetto to new towns, suburbs, and free prescriptions. A hundred years later and large areas have never recovered.

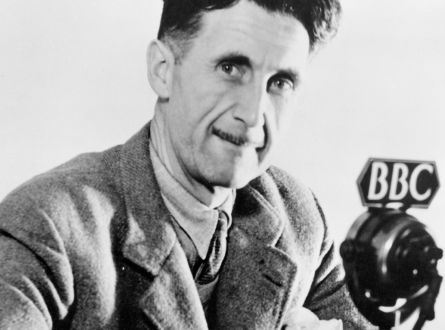

In my teenage years, my dad (pictured left, middle photo) told me to read everything that Orwell had written. It would, he said, be “educational” for me. He had lived through the times Orwell wrote about, had optimistically but briefly planned the new post war world with comrades and had resigned from the Labour Party in the late 1950’s on a point of principle. He told me that I should read books and escape.

In my teenage years, my dad (pictured left, middle photo) told me to read everything that Orwell had written. It would, he said, be “educational” for me. He had lived through the times Orwell wrote about, had optimistically but briefly planned the new post war world with comrades and had resigned from the Labour Party in the late 1950’s on a point of principle. He told me that I should read books and escape.

But I was a callow youth and so I rejected my father’s instructions and, at school, opted for DH Lawrence, Thomas Hardy and J.B. Priestley. At university, on a whim, I borrowed all the Orwell books from the library and read them in the summer sun. The luxury of reading time was short-lived. I soon had to get a proper job, an improper mortgage, and an aspidistra.

Orwell groundswell

Orwell groundswell

Orwell was born in 1903 and went to Burma in 1922, where he joined the Indian Imperial police. It was a job for which he said he was totally unsuited and so, at the beginning of 1928 while on leave in England he gave in his resignation in the hope of being able to earn his living by writing. He says:

“I did just about as well at it as do most young people who take a literary career that is to say not at all; my literary efforts in the first year barely brought me in 20 pounds”

Down and Out in Paris and London was researched in the late 1920’s by Eric Blair and published as his first full length book under the pseudonym George Orwell in 1933 by Victor Gollancz, a prolific publisher in the 20th century whose own life is worthy of attention. A British publisher and humanitarian, he also set up the Left Book Club and in 1945 he set up the “Save Europe Now” organisation to campaign for the humane treatment of German civilians. It is quite possible that there would have been no George Orwell without Victor Gollancz; publisher, and friend. Letters between them reveal Orwell’s inherent pessimism and fears, contrasted with Gollancz’s faith in humanity. In 1940 Orwell wrote to him:

“It is quite possible that freedom of thought may survive in an economically totalitarian state. We can’t tell until a collectivised economy has been tried out in a western society and what worries me at present is the uncertainty as to whether the ordinary people in England grasp a difference between democracy and despotism well enough to want to defend their liberties. One can’t tell until they see themselves menaced in some quite unmistakable manner. The intellectuals who are at present pointing out that democracy and fascism are the same thing depress me horribly. However, perhaps when the pinch comes the common people will turn out to be more intelligent than the clever ones. I certainly hope so”.

Orwell’s colleagues were writers and publishers of literary magazines. Some like John Middleton Murry was a well-known pacifist, others such as Sir Richard Rees set up the Workers Educational Association in 1925.

This crowd of people around Orwell were part of a movement. Publishing, writing, journalism, and presenting an international, left wing alternative. From the 1920’s to his death in 1959, Orwell was on a mission.

Down but not out

This book combines memoir with a study of poverty and homelessness in two European cities in the inter war years.

Orwell wanted to expose the knowledge of poverty to an upper- and middle-class readership. He believed that one this iniquitous situation was made visible by his journalistic skills, then the powers-that-be would be shamed into supporting a new system that enabled full employment as a means to eradicate poverty.

He travelled around London and Paris in 1927 and 1928. His first published essay was called “The Spike” based on tramping around London’s workhouses. He had donned ragged clothes and slept overnight in East London spikes – dosshouses. This “field work” was done before he went to Paris.

His language, his anthropological methods, his fusion of documentary and fiction came under attack from all quarters at the time and ever since. Like any great independent thinker, he was both co-opted and rejected in equal measure by the multi-faceted left and the resolute right. People can get what they want out of his writings, and that’s no bad thing.

For me, the book is without a doubt, a defence of human dignity. Orwell liked to think about the lost people, the underground people, tramps, beggars, criminals, and prostitutes and imagine the good world they inhabited down there. He liked to think that beneath the world of money there is that great underworld where failure and success have no meaning. Like some of his characters, this was where he wished to be; down in the ghost kingdom where dignity no longer mattered. First reading this in 1980’s Liverpool, I wanted to live on the surface where the superficial dream played out.

Boris and the Russians

Boris and the Russians

Orwell describes in anecdotal and biographical detail, a set of characters who he briefly shares his life with, in Paris and London hotels, lodging houses, restaurants and shops. From the former Russian soldier Boris, to Paddy with a deep knowledge of charity in East London, to Charlie who describes his violent rape of French women as “the true nature of love”. He meets cocaine dealers, rag merchants, street artists and doorkeepers from Armenia . He meets vicars who serve free tea and give passionate sermons about the importance of being saved as well as communists who refuse to work. The women are fat with cow-like faces and breakdown in tears when drunk. From opera singers to the “mostly mute sewer workers”, this is an elaborate, yet brief visit fuelled by daily drunken stupors.

The book starts to reveal the literary and societal hierarchies, the animal references, and the layers of humanity that he builds into the dystopian visions of ‘1984” and “Animal Farm” . It’s a great book for telling us about Europe between the wars, but also because of what can it tell us about today, in particular homelessness?

There is a strong sense of despair and of course dystopia in all his work; happy endings are few and far between. His expose of poverty, vice and corruption offers few solutions especially once Orwell sees how free speech, liberty and truth can all be so conditional in the post war world. He was driven to shed light on this underworld so that the authorities would attend to it, but then he despaired of how those powers might be exercised.

He treated all his characters and research work as “field trips”. A sort of David Attenborough at the bottom of the ocean. Some Journalists suggest it still has so much to tell us. If only the world and “WE” within it could be more just, they say. In Orwell’s cities he was revealing something society didn’t see. Now we do see it all the time in that there is a desire to promote more novels, poetry, photographs – an evidence base of homeless people – that will allow us all see what’s what and deal with it.

Orwell: Ends Well?

Orwell in general and this book in particular have been revisited over and over. His fictions and phrases have entered international language. To be Orwellian is to be destructive of welfare and a free and open society. “Room 101”, “2+2=5”, “Ignorance is Strength” are all understood and reused in the modern “Ministry of Truth”. Maybe best known is “Big Brother”. In the Year 2000, the estate of George Orwell sued Endemol (whose founder made $1.5 Billion creating the TV show Big Brother) for copyright and trademark infringement. They settled out of court.

“Down and Out Live” took place in 2018 – with Simon Callow, Jon Snow and Jack Monroe reading from the book. Journalist Hannah Price wrote in The Independent that

“Orwell is a renowned progressive thinker, yet his good intentions occasionally mask questionable practises. When he sells his gentleman’s clothes to adopt the costume of the poor, a modern audience can’t help but query this methodology… I was delighted to discover that the book still burns brightly with the sense of unfairness and the desire to create change. The book both illuminates the huge change between 1933 and now and exposes horrifying similarities as all well reveals the cruelty of a lack of workers’ rights where livelihoods are lost overnight, or jobs are not secure from one day to the next day. A modern audience cannot help but compare zero hours contracts. Apart from his political intentions Orwell’s appeal as always rested in its brilliance as a writer his ability to distil vast ideas or injustices into perfect phrases Orwell wrote in his diary that what he most wanted to do was to make political writing into an Art.”

Maybe every generation will reinvent Orwell and rewrite his intentions and motivations. He was indeed a great writer and journalist, but he also wanted to change the world and at times fought to do so. He observed the time and place he lived in and recorded it for us. But he was not a passive artist.

Homelessness in UK cities and towns has come under the spotlight again in very recent years as changes in welfare benefits, the recession and other aspects of social breakdown have led to greater numbers of rough sleeping visible on our streets. This is most certainly nothing new. We didn’t count homeless people in the 70’s and 80’s. We knew many were from the forces and the newly “broken homes” and still are. In Liverpool after the blitz, there were 70,000 homeless people. YES – you read that right. In 2018-19, Liverpool recorded a total of 899 instances of rough sleeping. But in the immediate post-war, slums (homes) were destroyed families were displaced and desperate, and home-building didn’t keep up with the demand.

In 2020, City Mayors have homeless action network strategies, initiatives and monthly counts supported by businesses and celebrities. During this Orwellian lock down, a funding strategy of “everybody in” has led to all homeless people being moved into hotel rooms whilst the kitchens are mostly closed! There is a political spat about the state funding model. No one wants to see the poorest and most ill people in our society chucked back out onto the streets. After all, when the furlough and mortgage “holiday” ends, how many others’ homes will be commandeered?

In 2020, City Mayors have homeless action network strategies, initiatives and monthly counts supported by businesses and celebrities. During this Orwellian lock down, a funding strategy of “everybody in” has led to all homeless people being moved into hotel rooms whilst the kitchens are mostly closed! There is a political spat about the state funding model. No one wants to see the poorest and most ill people in our society chucked back out onto the streets. After all, when the furlough and mortgage “holiday” ends, how many others’ homes will be commandeered?

The first half of the 20th century was hugely contradictory. The most dynamic and destructive, momentarily hopeful, and yet eternally filled with doubt. Starting with the end of the Victorians and ending with the start of a “golden age of capitalism”; the birth of the baby boomers, the Barbie Doll, birth control, and modular construction.

The wars blew apart so much of humanity across the globe and was, of course, deeply felt by everyone of that generation. Orwell died of tuberculosis on 21 January 21, 1950. He never witnessed the psychedelic sixties, the moon-landing, the building of the Berlin Wall and Coronation Street. But he understood how humanity might respond.

To understand this book, one has to appreciate its position as a snapshot of early 20th century history. Make of it what you will, I highly recommend reading everything George Orwell ever wrote.

.