Book Bites: “Voices from the Rust Belt” by Anne Trubek (ed)

Reviewed by Steve Nash

In case anybody needs reminding, the 2016 presidential election result was seen as being won in the key states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Michigan. Clinton polled 62 million votes and Trump 61 million, but because of the way that the electoral college system works, especially in these key marginals, it heralded a victory for Trump.

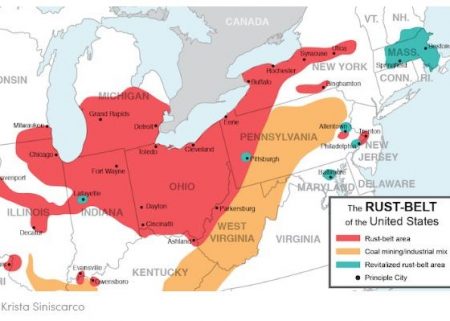

He also won in Florida and Texas and the more prosperous southern and western states, by the way, but it was the nature of this victory that placed the focus on the Mid-West and what had become known as the Rust Belt. A phrase coined by Walter Mondale in 1984 – something I was unaware of until reading this fascinating book; an anthology edited by Anne Trubek. Trump himself drew attention to the Rust Belt in his inauguration speech painting a lurid picture of industrial decline. “One by one”, he said, “the factories shuttered and left our shores, not even with a thought about the millions of American workers that were left behind”.

Voices from the Rust Belt is essentially a reaction to that election result. When you look at the website for Belt Publishing you find the following claim. “The question ‘What Happened?’ has been asked of the Rust Belt more than ever before. But it’s the same question the Belt has been answering for the past 4 years”.

The claim is that by a writer’s ability to bear witness and to render experience we gain greater insight and are provided with a more nuanced understanding of an area and of a people. As Trubek puts it in the introduction, the writers “resist the urge to make of this place a static, incomplete cliché, a talking point or a polling data set”.

I think we have to ask whether it answers its own question, “What Happened?” in 2016. There is undoubtedly some very fine writing in this book. But is the writing too subjective and patrician (or to use a phrase from one of the writers, a “narrative therapy”)?

There is a structure to the book moving from Growing up, Day to Day, Geography, to Leaving and Staying. There are some intensely subjective essays; memories of childhood and youth and also more objective commentaries around urbanism and development? Each writer offers a different, unique and compelling perspective.

Many chapters have a poignancy to them which leave you with a real sympathy for the struggles of the area – the huge geographical area of the Rust Belt -and its people. Other writers can be quite aggressive: justifiably angry about what has happened to jobs and living conditions over a long period. There are tentative attempts at answering some of the challenges facing the region, but above all, this is a literary response to the fall, and potential rise, of old industrial town and cities.

In the chapter, A Girl’s Youngstown, Jacqueline Marino conjures up the duality of childhood experience. “The Youngstown of my past is two cities, one safe, leafy and full of promise: the other scary, dirty and stifling. In my memories, in me, both remain.” In the chapter, The Kidnapped Children of Detroit, Marsha Music decries the “restrictive covenants” that aided the suburban exodus of the white population from the 1960s onwards. Henry Louis Taylor writes disparagingly of a city being created for “educated millennials, the creative classes, refined, middle aged urbanites and retired suburbanites”.

One is left with a mix of emotions. Often one writer’s perspective clashes with another, seemingly reflective of the tumult of the city. There is a sense within the more urban-focused works that suburbanisation and mobility have been negative factors and yet a return to the city is also problematic. New immigrant voices offer hope, bringing commerce and community back to the city; while other writers cite the ecology of a non-industrial city in a positive light. At times there is a feeling of writers proving to their counterparts in New York and the West Coast that life in the Rust Belt is just as complex and conflicted as their own and that maybe there is less that divides them after all. It is definitely a complicated, thrilling, depressing story, beautifully told by many of the contributors.

Trubek claims that there has been a narrative inequality when writing about the Rust Belt with too much of a concentration on manufacturing. The Trump narrative if you like. But is that true? The shock of Trump’s election victory was that 61 million Americans had rejected the dominant liberal narrative and values that seemed to have no resonance for them in their daily lives. Their voices – the voices of the so-called Deplorables – had been largely silenced, vilified, and ignored up to that point. Does this book address that voicelessness, or is it another example of them being spoken for, rather than listened to? Indeed, they rarely have a voice in the arts and literature. If a modern version of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man could be written today it surely would be written from the perspective of these 61 million Americans.

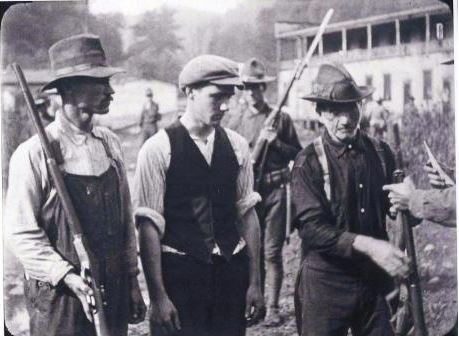

When Trump campaigned for the coal industry in West Virginia he knew he was reaching out to these disillusioned people. The chapter, King Coal and the West Virginia Mine wars museum was instructive whereby we seem to be more comfortable with the historical class conflicts of the past than with the real living coal miners of the present? Incidentally, there are only 50,000 working miners left in the USA, so is this merely romantic symbolism?

There is another thread that runs through the book that explores the way that different generations view the past and the present. Jason Segedy’s essay about Akron, Ohio, the “Rubber capital of the world” made some good points: “The late 1970s and early 1980s was the end of one thing, and the beginning of (a still yet to be determined) something else. It was a great economic unravelling, and we are collectively and individually still trying to figure out how to navigate through it, survive it and ultimately build something better out of it”.

The collapse of American heavy industry climaxing in the recession of the early 1980s has cast a long shadow. At the time it was justified as a brutal but necessary change. Later on the industrial world pre-1980 was recast as dirty, polluting, sexist and racist and good riddance to all that. The book poses some new questions for us as we now see that there are consequences to the hollowing out of American industries and cities.

Without romanticising or demonising the past, would it be useful if we could at least agree that the industrial world before 1980 did, at least, give working people meaning, and gave them some political weight in society that hasn’t been replaced since. Examining things from that perspective might also help in answering the question what happened in 2016?

Reviewed by Steve Nash, contributor, The Lure of the City

Buy the Book Trubek, A. (2018) “Voices from the Rustbelt“, Picador (New York), pp247 is available here.

.