Straight Line Crazy – A Review

Why, I wonder, has a play about New York’s pre- and post-war urban design opened in London to full houses and rave reviews? It’s a 2-hour 20-minute foray into the work of several key protagonists involved in the design of US freeways, bridges, housing, and public transport systems in the 20th century, and not exactly the kind of escapist fayre we might expect in post-Covid theatreland.

Indeed, it’s all a bit niche, you might think, but this production at the Bridge Theatre, London written by David Hare, directed by Nicholas Hytner, and starring Ralph Fiennes, deals with the battles to “modernise” New York and recounts the life and times of controversial urbanist Robert Moses (played by Fiennes). In a 40-year career, Robert Moses was allegedly the most powerful man in New York; the man who pushed through masterplans for a grid of new highways, bridges, urban parks (or “porks” as Fiennes repeatedly enunciates in a New Yoik accent), beachfront real estate, housing projects and two hydroelectric dam projects; as well as ensuring the construction of the Lincoln Center, Shea Stadium, and New York World’s Fair. It has become a well-established saying that if you have ever driven on a highway or a bridge in New York, you’ve availed yourself of the life’s work of one man.

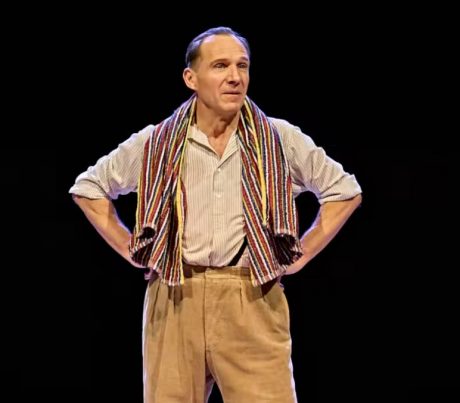

“Straight Line Crazy” is a play in two Acts, each separated by some 30 years (awkwardly characterised by the merest dusting of grey on the actors’ wigs, and an almost imperceptible shift in fashion). The first half details Moses’ rise; the second, his fall from grace and it is the latter period that has tended to prevail in the public consciousness. Even today, it is the “despotic”, “autocratic” nature of the Moses that is remembered (predominantly as a result of the 1974 biography by Robert Caro). Fiennes regularly adopts Moses’ pose from the cover of Caro’s book: an unelected visionary, hands on hips, bestriding the city. In his heyday, Moses held 12 official positions in the Greater New York city area – all unelected – including New York City Parks Commissioner. He was Emperor of all he surveyed.

“Straight Line Crazy” is a play in two Acts, each separated by some 30 years (awkwardly characterised by the merest dusting of grey on the actors’ wigs, and an almost imperceptible shift in fashion). The first half details Moses’ rise; the second, his fall from grace and it is the latter period that has tended to prevail in the public consciousness. Even today, it is the “despotic”, “autocratic” nature of the Moses that is remembered (predominantly as a result of the 1974 biography by Robert Caro). Fiennes regularly adopts Moses’ pose from the cover of Caro’s book: an unelected visionary, hands on hips, bestriding the city. In his heyday, Moses held 12 official positions in the Greater New York city area – all unelected – including New York City Parks Commissioner. He was Emperor of all he surveyed.

The Daily Mail described Moses as “one of America’s worst megalomaniacs” and just so that we understand that Moses is undeserving of our empathy, in the first scene he casually refers to “kikes and wops, living in the tenements.” Presumably, this was deemed to be a safe choice of racial slur as there is no possible way that authentic racist parlance against Black Americans at the time, would be permitted. London’s theatre-go-ers would have choked on their Chardonnay but anti-Semitic (and anti-Italian) sentiments are dramatically acceptable, it seems.

Of course, the script, derives – inevitably – from Caro’s book* and having to compress 1300 pages, and a relentlessly creative life, into 2 hours, relies heavily on caricature. Many of the tropes about Moses’ racism (building bridges too low for buses – the common means of transportation for poor New York Black people – while facilitating wealthy white car-owners) have subsequently been refuted but still appear in the text.

There are clearly sign-posted allusions to our contemporary populist moment. Admittedly Hare doesn’t descend into crude analogies with Donald Trump, et al, but the programme says that Moses’ single-mindedness imposed an “iron will (which) exposed the weakness of democracy in the face of charismatic conviction.”

The play explores the conundrum of the value of experts (including architects) who single-mindedly drive through visionary solutions for the benefit of the people, but without asking them, predominantly because they believe that ordinary people won’t be able to comprehend what is good for them. Rather than convincing the people, of course, Moses (Fiennes) says: “We break Manhattan, or it breaks us.”

Variety magazine correctly observes that the play is “painfully reliant on exposition” to drive the story along. Sometimes through soliloquies, sometimes by awkwardly contrived dialogue. Jane Jacobs, the woman who made her name as Moses’ nemesis, only appears as a marginal character to narrate the occasional change of scene. In this production, Jacobs’ historic role is transferred to Maria, a young, idealistic Black assistant in Moses’ office. It is Maria who confronts Moses while Jacobs is a bit-part player dismissed as just another middle-class, white NIMBY. Maria is clearly a metaphor for change: for Black empowerment against “white” diktat; the Rosa Parks of white-collar workers. The factual reality of Jacob’s battle against power wouldn’t have signified as much, it seems.

The play revisits a critical period in America when public transport was ousted by the car, the era of racial empowerment, the challenge to established old men by smart young women. These contemporary issues form the basis for the revival of this historical narrative that asks whether we are seeing the end of an establishment confronted by an emergent protest culture. The fact that the protest culture in contemporary society is even less democratic than what went before, is less tolerant of developing much-needed infrastructure or catering for material needs, is unaddressed. But these have significant implications. As Moses (Fiennes) concludes: “Once America ceases to believe it can make the future better, we cease to be.”

The review in Variety magazine claims that “subtext… is almost entirely absent.” I couldn’t disagree more. For me, subtext is everywhere in this production. By declaiming the era of old white men as an out-of-touch club of Tammany Hall demagogues, much of the historical and infrastructural brilliance of Moses’ intervention is lost or parodied.

________________________________________________

*There is no reference to Robert Caro’s book in the programme notes.