India, China: Talk of the town

By Austin Williams | Feb 19, 2013

As an architect living in Suzhou, just outside Shanghai, I have become blasé about the skyline being transformed before my very eyes.

As an architect living in Suzhou, just outside Shanghai, I have become blasé about the skyline being transformed before my very eyes.

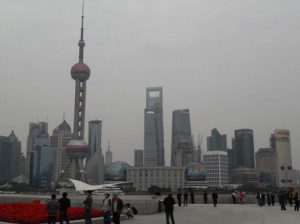

The classic view of Shanghai’s towering waterfront may not represent great architecture, but it’s impressive all the same… and constantly improving.

In most cities across China it is the same story: high-speed construction activity, modernisation, transformation and skyscrapers everywhere. There is a palpable sense of opportunity pending — what the émigrés to America must have felt when arriving in New York 100 years ago. While many Western commentators point to the failures (the accidents, the pollution and the corruption) with an unremitting Schadenfreude, China marches on. Where else can you watch a modern city grow and change in real time?

Where else, indeed?

I hadn’t been to Kolkata for 30 years. Then, it had been a crumbling, anarchic, messy, congested, dusty, frantic confusion of people, cars and animals. I was looking forward to seeing how a country with similar economic growth rates to China had fared in its architectural aspirations. Tellingly, almost nothing had changed. The main city still combined a lack of basic infrastructure and a shaky superstructure. Its sense of urban cohesion seemed to reflect a desperation to hold things together rather than any real conscious urban strategy. However, instead of central-urban regeneration, the real changes were happening on the fringes, the satellite cities and the new town developments. This is repeated throughout India: from Gurgaon to Navi Mumbai to Lavasa, Pune.

In short, urbanism in China is clean, sanitised and exciting; India’s is grimy, raw… and exciting. Undoubtedly, China’s “ruthless” ambition to build the future comes with caveats, but so do India’s bureaucratic, fragmented ambitions. In both places, construction standards are low, workmanship is poor (and so are the working conditions), air quality is bad and the architecture leaves a lot to be desired. But that is the price of progress and simply to attempt such a huge range of urban transformations — from within urban centres or outside the existing urban fringe — is admirable. “Make no small plans,” said one of the world’s first masterplanners, Daniel Burnham. We all know that mistakes will be made, but India and China prove that that is no excuse for not trying.

Many people point out that whereas China has the power to remove populations, impose its Central mandate and eat up small towns to create new cities, India seems to prefer to leave existing town centres alone, avoid confrontation and shift the development elsewhere. Obviously, India is not averse to kicking people off the land because, actually, if you are going to develop major urban projects, some people are going to be upset, while hopefully many more people will reap the benefits.

As a consequence, some commentators have likened these urban differences to the political polarisation between India as the world’s biggest democracy and China, the world’s biggest autocracy. Citing India’s urban chaos and the Chinese Communist Party’s success at becoming the world’s biggest economy, support for non-democratic urbanism, autocratic mayoral powers — or “benign dictatorship” — is growing. This is troubling for anyone interested in preserving the civilisational gains of democratic discourse, and represents a purely pragmatic response to urbanisation. It also misses the point.

Cities are different. For example, in Daniel Brook’s new book, The History of Future Cities, he argues that Mumbai (like Shanghai and Dubai) was founded on the promise to build the future. They were designed as world cities. Not so for Delhi, for instance, which has maintained itself as a historical remnant: a city of the Raj, seat of governmental urbanism.

Secondly, China has compressed 50 years of urban development into 20, while India has dragged 20 years of development over 50. India’s evolution versus China’s “revolution” means that there are issues of land use, property values and urban identity to reconcile in India as opposed to the Chinese model, which is a completely different social construct. China’s tabula rasa attitude to urban development is due, in part, to the fact that it’s true: politically and socially they believe that they have a clean slate.

Actually, even though China is allegedly building 20 cities a year for 20 years, it, like India, is not urban enough. The World Bank estimates the urban population in India to be around 31 per cent, which is smaller than Africa. China is just 50 per cent urban. However, the United Nations considers a modern society to be one with around 70-75 per cent of its population urbanised, so it seems that both China and India still have a long way to go.

But what’s more important than statistics is that both in China and India there is, at least, a visionary desire to achieve improvements in the urban condition. A visit to Shanghai’s urban planning museum, for example, contains a vast model of the city which maps out the existing, but more importantly, the planned developments over the next 20 years. Similarly, the opening lines of Delhi’s Master Plan 2011-21 state that the intent is to “make Delhi a global metropolis and a world-class city” in 10 years. In these two developing nations, the model is “the future”, so they should be forgiven much.

In Britain, by contrast, the Prime Minister has just announced his plans for “urban villages” modelled on Victorian-style architecture drawn up by Ebenezer Howard in the 19th century. No city has been built in the UK since the end of Empire. So whatever mess China and India make in getting there, at least they have an eye on the future. The West is happy merely to recreate the past.

——-

This article first appeared in The Asian Age

Austin Williams is the co-author of Lure of the City: From Slums to Suburbs and director of the Future Cities Project. He teaches architecture and urban studies at XJTL University in Suzhou, China. Email at futurecitiesproject@gmail.com