The Anti-Human Eco-City

By Paul Thomas | 20 April 2014

By Paul Thomas | 20 April 2014

Before attending this lecture on The Anti-Human Eco-City at Leeds Met, I’d heard of them but was unsure what they were. Apparently, I was not alone. According to the speaker, Austin Williams, Associate Professor of Architecture at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, China, there is no agreed definition of what an eco-city is; there are very few that have been built; and the most famous one, Dongtan in China, does not exist.

For Williams though, one thing is for certain: an eco-city is one where the interests of people are considered second to nature, if they are considered at all.

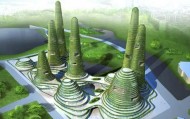

The one thing missing from the plans he showed of proposed (or long-since abandoned) eco-city projects was people. Plenty of trees and foliage covered buildings, but none of the signs of human life that one would normally find in artistic impressions of architectural plans. The one exception to this rule was the proposal by green architect-of-the-moment, William McDonough, for Huangbaiyu in China — a plan which depicted people working in rooftop paddy fields. While people normally move to cities to escape rural life, Williams notes that in McDonough’s vision people are freed from neither backbreaking work in the fields, nor their semi-feudal relationship to their landlords.

The eco-city sees the environmental orthodoxy of “sustainable development” applied to planning and design. An eco-city, as defined by Wikipedia, is “a city built off the principles of living within the means of the environment”. The problem with this is that there are few better manifestations of humanity overcoming natural limits than the development of cities. In addition, it seems to me that an eco-city represents the same conquest of nature as any other city, but just in denial — and with literally greener and people-less plans.

-

Tianjin, China… empty Utopias

For Williams, the lack of people in the eco-city vision is no accident. Rather it reflects a very contemporary ‘Malthusian discussion’ in which humanity is seen as a problem that the planet faces: there are, apparently, just too many of us, consuming too much stuff. Eco-cities are therefore an attempt to manage and socially engineer people’s behaviour to rein-in and minimise their impact on the planet — mainly, it seems, by discouraging car use in countries where people have only just got off their bikes.

It is not just the footprint of those expected to live in eco-cities that is reduced by eco-cities, but that of architecture itself. As Williams says, architects have traditionally looked to ‘make a statement’ and ‘leave their mark’ on the world — an idea he urged the young architects in the audience to re-embrace. While firmly believing they should “go out and build stuff”, Williams notes that, to do so, they need to first “reject the concept of sustainable development and promote its opposite – development”.

This article first appeared in ‘Freedom in a Puritan Age’

Paul Thomas is co-organiser of the Leeds Salon