Film Review: ‘City Visions’ #2

Matthew Bloomfield | 2 October 2014

Matthew Bloomfield | 2 October 2014

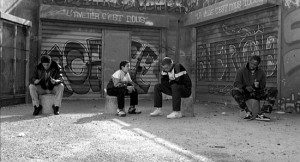

‘La Haine’, Dir. Mathieu Kassovitz

Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine follows the lives of three young men in the 24 hours after a riot tears through their home in the banlieues of Paris. The film was inspired by rioting in 1993,sparked by the ‘accidental death’ of Makome M’Bowele who died while in police custody.

He was shot while hand-cuffed to a radiator.

La Haine‘s three protagonists provide a cross section of the demographic in the deprived suburbs around French cities; Black, Maghrebi and Jewish. The diversity in France’s population is due to its previous policies of granting citizenship to members of its former colonies. However, once in France these migrants would struggle to find work or housing, and faced widespread and institutionalised racism. A 2008 survey puts the proportion of first and second generation migrants in France at 20% of the whole population, 4 million of whom are from North Africa. Given the birth rate within the Maghrebi population is higher than in other demographics, over the coming years their significance will grow in relationship to the overall population.

The first half of the film takes place in the banlieues, typically schemes of comprehensive redevelopment that have actually concentrated and aggravated social divisions. While criticism abounds for councils that have failed to address the failings in their housing stock, actually not every banlieue is in the same situation. For every Clichy-sous-Bois, where the widely reported riots of 2005 began, there is also a middle-class Versailles. In fact, despite becoming a byword for rough neighbourhoods, in reality banlieues are actually just administratively separate communes. However, in the example of Paris, where 80% of the population are banlieusards not counted as living in the city proper, many working-class neighbourhoods have only limited funds to address the host of issues facing them. This can have the effect of exacerbating social divisions.

As the narrative follows Vinz, Hubert and Saïd, we are given a strong impression of daily life on the edge of society, including financial struggles, drug dealing and gun-crime. But the film also clearly depicts the emphasis on family and friends that this adversity prompts, as well as the resilience born out of it.

This is heavily contrasted by the second half of the film that sees the protagonists in the centre of Paris, where “the pigs are so polite…” but the people are unwilling to accept the presence of three men who are clearly unaccustomed to moving in such affluent circles. Later, when the three are sat in an empty shopping centre, the homogeneity of their surroundings presents a disparity with the earlier scenes in the shabby but vibrant social housing.

The success of Kassovitz’s depiction of urban deprivation won the film a slew of awards and threw the topics of police brutality and lack in integration into the limelight. The clarity with which it illustrates these issues even prompted Alain Juppé, French Prime Minister from 1995 -97, to commission a compulsory screening of the film for his whole cabinet. The problems in the banlieue were clear then and it was time for direct action to rectify the inequality.

Regrettably, nearly two decades after La Haine was released, the situation does not seem to have improved greatly. Moreover, we have seen rising inequality across the globe with the richest few able to increase their wealth whilst unemployment soars to record highs. The context in which the film takes place bears direct comparison to the recent events in Ferguson, Missouri. It is a sad hypocrisy that two countries that define themselves through liberté can allow their most vulnerable to be systematically victimised.

Throughout the film, different attitudes towards this lack of freedom are expressed. Vinz operates within a strict us versus them dogma whereas Hubert is willing to work within the system, taking a grant and opening a gym to take young men off the streets. The dramatic finale leaves us uncertain as to whether Hubert has killed or been killed. Despite his being the strongest positive influence in the narrative, either his righteousness was not enough to save him and his neighbourhood or, alternatively, it was not enough to prevent him from murdering a police officer in an act of revenge. Regardless of the outcome of this Mexican stand-off we can be sure that there will be more rioting this night.

Ultimately La Haine is not a direct criticism of conditions in the banlieue or of the inner city elite. Instead it protests against the inequality between them and the machinations that perpetuate and exacerbate this gulf, whether that be heavy-handed policing, economic forces permitted by government or the prejudices of ordinary people. What is being fought for is not so much class mobility, but cultural mobility whereby young black men won’t be frowned at in art galleries and well educated Arabs won’t have their job applications passed over because of their surnames.

La Haine is part of the series City Visions at the Barbican September / October 2014

Matthew Bloomfield is an architecture student struggling to get by in London.