Wang Shu. Who?

Wang Shu burst onto the world’s stage with two projects that caught the media’s attention and lined him up for the awards and citations that have made him a household name … in architects’ houses, at least. These were the Ningbo History Museum (2008) and the Xiangshan Campus in China’s Academy of Art (2007). These episodic buildings are regularly referred to in ways that fans of the US sitcom Friends might recognise: ‘the one with lots of random bricks’, ‘the one with the external walkways’. (see below)

Wang Shu burst onto the world’s stage with two projects that caught the media’s attention and lined him up for the awards and citations that have made him a household name … in architects’ houses, at least. These were the Ningbo History Museum (2008) and the Xiangshan Campus in China’s Academy of Art (2007). These episodic buildings are regularly referred to in ways that fans of the US sitcom Friends might recognise: ‘the one with lots of random bricks’, ‘the one with the external walkways’. (see below)

Both projects were instrumental in Wang being presented with the Pritzker Prize in 2012. At that ceremony, Lord Palumbo lauded Shu’s ‘distinctive architectural language that speaks to everyone’. The Pritzker jury saw Wang’s work as ‘deeply rooted in its context and yet universal’. Such plaudits were rather different to local responses in China. ‘When we heard that he’d won the Pritzker Prize, we all laughed because we thought it was a joke,’ said one of Wang’s former students, ‘he isn’t really that good.’ So how can we reconcile this gushing yin with this sceptical yang?

Palumbo had effervesced that: ‘the buildings of Wang Shu are bargains between monumentality and intimacy; past and future; painterly and tectonic; public and private space’. This was less a speech than a Daoist chant, as much intended to chide Western architects into new ways of thinking, as to praise China’s wunderkind. For Critical Regionalists especially, the caricature of harmonious Chinese architecture – apparently blending old and new – appears to be the holy grail, with Wang Shu its Knight Templar.

Western society is regularly criticised for its silo mentality, reflected in competing visions about such things as architecture and society; China’s philosophical traditions, however, are often characterised by their inscrutable ability to see the complementary rather than the contradictory nature of dualism. Nowadays, some Western commentators seem willing to look enviously upon China’s ability to get things done. Western democratic planning processes are dismissed by many as stifling creativity, while Chinese single-mindedness is perceived as enlightened. Wang Shu has emerged at a time when every architect wants a Chinese friend.

Wang was born in 1963 to middle- class parents: his father, a musician, and his mother, a teacher and librarian. He grew up in Ürümqi, the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in remote far west China, and though his childhood coincided with the Cultural Revolution, he read widely and was interested in painting, crafts and literature. When he rebelled at his parents’ insistence that he should study sciences, they compromised on architecture at Nanjing Institute of Technology (now the Southeast University). He graduated in 1985 and officially completed his master’s degree in 1988, although he admits that he didn’t get his master’s certificate. Speaking on Chinese TV, he explained: ‘I was very conceited. Even though I had been thinking about the subject for three or four years, I finished my [master’s thesis] in only 15 days. Unfortunately, I wrote the start and finish dates on the paper and they thought that I hadn’t spent enough time on it.’

Whether this was what gave him pause for thought about the speed of production in China, or whether it was his observations about the integrity of slowly crafted accretions on indigenous buildings, from 1990 he effectively withdrew from practice for 10 years to train himself in craft- based skills, vernacular architecture, construction techniques and an appreciation of natural materials. He emerged with a PhD and a desire to create an idiom in which traditional culture merges with the modern world, playing with memory, natural elements and reclaimed materials.

Wang Shu is no William Morris.

Even though they both have all the hallmarks of Romantics who concur that the design, manufacture and use of a product (a building) are integrally linked, Morris was a socialist, whereas Wang is simply looking for cultural rather than political change. Morris wanted to change the world, while Wang is alarmed at the speed with which the world is changing. (In fact Wang has been cited as the poster boy of the Slow City movement.) Morris was into utopian politics, Wang is interested in identity politics.

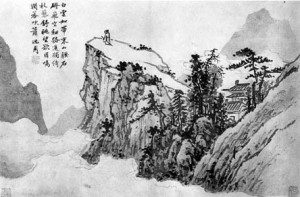

Wang used his reclusive decade to reinvent himself as ‘a scholar, a craftsman, and an architect, in that order’. He emerged as a self-professed member of the literati: Chinese intellectuals who used painting and poetry to display their erudition and superior cultivated status. From the Tang dynasty on, literati repudiated professional artistry for its dogmatic, learned skills, preferring to adopt the moral high ground by painting in a deliberately amateurish way. These literati proclaimed that they were not slavish Imperial court artists but artists who could express their spontaneous individuality. Their art was an expression of their freedom – as far as it could be – within the system: an expressiveness that prized honesty over realism. The original literati were the punks of the 10th century.

Early literati would display their art for discussion, their scrolls used in the way that books and newspapers were pored over in 18th-century coffeehouses. However, because these were evocative works of art and not political treatises (à la Western coffeehouses), the debate remained abstract. One Confucian scholar writes of literati work: ‘truth cannot be put into words, only through riddles or … an impressionistic feeling in poetic art format’. Wang Shu conforms to type here. His work is to be appreciated as a dialogue between man and nature. This is not the environmentalism that Western sustainability consultants crave, but an attempt at a more ethereal spiritualism that defies inquiry.

At Xiangshan campus, an array of buildings sit at the foot of the mountains. Rich in symbolism, the mountain has been an artistic motif for the rhythm of nature for a millennium and in case we don’t get the reference, the external walkways are literal reminders of the convoluted mountain paths beyond. The building is different, quirky, and creates an instinctively enjoyable architecture rooted in its place. The success of the building, though, is the thoughtful use of materials.

At Xiangshan campus, an array of buildings sit at the foot of the mountains. Rich in symbolism, the mountain has been an artistic motif for the rhythm of nature for a millennium and in case we don’t get the reference, the external walkways are literal reminders of the convoluted mountain paths beyond. The building is different, quirky, and creates an instinctively enjoyable architecture rooted in its place. The success of the building, though, is the thoughtful use of materials.

His Ningbo Museum uses local recycled materials – tiles, bricks and stones – and is a reference to the memory of a lost notional city. As a form it is commanding, but is also the embodiment of an anti- urban critique that derives from his perception that China is hurtling into urbanisation, riding roughshod over its cultural heritage. His use of recycled rubble from demolished homes was a propagandistic expression of that debate and, as a result, the building has become almost sanctified so that some of the naff bits are always overlooked.

Wang clearly wants to spark a discussion in China about the need for the amateur, the apprentice, the artist, as well as honesty to materials and to place. The practice (founded by Wang Shu and his wife Lu Wenyu) is called Amateur Architecture Studio because only creative autonomy, he says, will enable Chinese architects to make meaningful judgements that might start to counter the poor conveyor-belt architecture of many Chinese Design Institutes.

Wang clearly wants to spark a discussion in China about the need for the amateur, the apprentice, the artist, as well as honesty to materials and to place. The practice (founded by Wang Shu and his wife Lu Wenyu) is called Amateur Architecture Studio because only creative autonomy, he says, will enable Chinese architects to make meaningful judgements that might start to counter the poor conveyor-belt architecture of many Chinese Design Institutes.

He clearly has a point and is creating thought-provoking, intelligent architecture that is challenging the next generation. Chinese architecture students no longer shrug their shoulders at his name, or suggest that he is a bad designer, but sadly, many seem to like him primarily because he represents China on the world stage. Creative criticism – a political act of critique – is in its infancy in this country of tradition and deference. Wang Shu plays his part but it will take active engagement in ideas – rather than retreating, or worse, kowtowing – to confront the issues failing Chinese architecture.

This article first appeared in The Architectural Review