Church on the Beach

Austin Williams | 7 April 2016

Austin Williams | 7 April 2016

From Nantes to Naples, Bruge to Budapest, many key European cities have churches at their centre. Regardless of denomination, the centrality of these churches has tended to convey a certain historic gravitas, dignity and authority to the civic sphere. Originally built as bastions of power, tradition and religious dogma, churches have survived, in many instances, as the genius loci of urban space.

Recall Giambattista Nolli’s map that documented the open-ness of religious buildings and their associated porticos and piazzas. The rise of the public as a social force in mid-18th century Europe claimed these places for common use, beginning the democratisation of political and doctrinal space. However, even as the Enlightenment brought the triumph of reason and individualism to the civic square, so the church managed to retain, to some extent, its base of refuge, purpose and piety. The destruction of irrationality during the Enlightenment was not matched by the destruction of faith nor its physical expression. Ecclesiastical buildings in much of Europe proved far too robust.

China’s churches tell a similar story of survival. The central square in Harbin, for example, still houses the magnificent Byzantine, former Russian Orthodox, Saint Sophia Cathedral (although it is now an art gallery and not a religious building). The Gothic Jiangbei Catholic Church in Ningbo’s Tianyi Square marks the foreign concession period. The architecturally exquisite MooreMemorial Church designed by László Hudec in 1931 has pride of place on the corner of People’s Square in central Shanghai. More recently, the Seventh-day Adventist church in Nanjing (inaugurated in 2013) is a dramatic modern statement in the city centre that reflects the creeping acceptability of churches in China.

Effectively outlawed in China during the Cultural Revolution as a Western deviation, many Christians (even the officially approved ones) were persecuted and pilloried. While the Communist Party is more tolerant of the construction of churches and the independent evangelism of some churchgoers, expressions of religion are still often backstreet trades. Recent research claims that there are 3,000 “house churches” (unofficial independent churches set up in opposition to the state-sanctioned churches) in Beijing alone. Recently, 230 of these churches in Wenzhou were classified as “illegal structures” and torn down.

That said, relatively speaking, the church is flourishing in China. The pragmatism of the Communist Party seems happy to utilise the charitable compassion of Christian organisations to alleviate the pressure on an overstretched state sector. China’s Christian population is now well over 70 million, the second largest in Asia with around 60 million Protestants and 10million Catholics. To put it in perspective, the Chinese Communist Party has 88 million members.

However, an article in The Economist recently hinted that many Chinese people attending churches are not really religious but using these select venues for social networking in order to make contacts (guanxi) and do business with likeminded moneychangers. In Wenzhou, the town with the highest percentage of Christians, churches organise meetings to explain various “biblical” approaches to getting rich.

However, an article in The Economist recently hinted that many Chinese people attending churches are not really religious but using these select venues for social networking in order to make contacts (guanxi) and do business with likeminded moneychangers. In Wenzhou, the town with the highest percentage of Christians, churches organise meetings to explain various “biblical” approaches to getting rich.

The other non-religious role of a church in China is the wedding photo-op. Anyone who has visited the Disney nightmare that is Shanghai Thames Town will have noticed the earnest queues outside the GRP replica of Bristol’s Christ Church. Here, yet-to-be married couples adopt the perfect pose in front of the bolted front door. Meanwhile, Suzhou’s Dushu Hu church invites English-speaking believers inside, while loved-up Chinese atheists are snapped among the bushes.

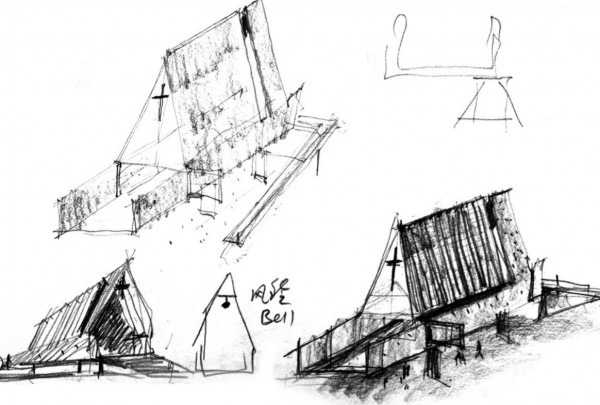

So given this context, what is the status of the stand-out, stand-alone church building situated on the beach in Nandaihe, northern China. It is certainly a thing of beauty: an objet d’art washed ashore, beached just above the waterline and allowing the tide to flood the exposed ground area. Designed by Vector Architects of Beijing, this small church is a few hundred metres from their previous waterfront building known as the Seashore Library. Architect Dong Gong says: “The sea level (in this location) is relatively stable and predictable, which helps us to decide the location precisely.”

The building is reached from a long concrete walkway that emerges out of the surrounding heathland. The path crosses the sand in a straight line to the grand entrance staircase. Even though (one suspects) that many visitors will approach the building from the beach to the south, the front elevation is designed as the culmination of the Modernist promenade architecturale from the west. From a distance, the building sits on the shore with the dramatic backdrop of the Bohai Gulf. Moving closer and the building cannot be criticised for blocking the views as the wide stairs have been bisected by a walled opening that allows visitors to keep a constant view of the sea ahead. In typical Chinese fashion, it frames the seascape.

The building is reached from a long concrete walkway that emerges out of the surrounding heathland. The path crosses the sand in a straight line to the grand entrance staircase. Even though (one suspects) that many visitors will approach the building from the beach to the south, the front elevation is designed as the culmination of the Modernist promenade architecturale from the west. From a distance, the building sits on the shore with the dramatic backdrop of the Bohai Gulf. Moving closer and the building cannot be criticised for blocking the views as the wide stairs have been bisected by a walled opening that allows visitors to keep a constant view of the sea ahead. In typical Chinese fashion, it frames the seascape.

Each elevation has been designed for aesthetic drama: the front elevation displays the faux mass of the building which is a steeply pitched monocoque structure held aloft on thin concrete columns; the side elevations are anchored at the western end allowing the structure to float 25metres over the sand (and sea); while the east elevation, viewed from the water, is a hovering triangular beacon of light. Underneath the overhanging upper floor is meeting place. Boarded with stepped seating, and tables it is suitable for open air services… or serving beer.

Each elevation has been designed for aesthetic drama: the front elevation displays the faux mass of the building which is a steeply pitched monocoque structure held aloft on thin concrete columns; the side elevations are anchored at the western end allowing the structure to float 25metres over the sand (and sea); while the east elevation, viewed from the water, is a hovering triangular beacon of light. Underneath the overhanging upper floor is meeting place. Boarded with stepped seating, and tables it is suitable for open air services… or serving beer.

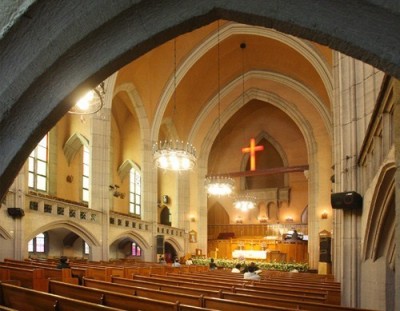

This ground floor area is unseen from the main arrival point. Instead, the visitor is drawn up the entrance stairs to the first floor piano nobile. The concrete roof over the landing has a narrow slit that separates it from the main body of the church, creating an informal porch. Entering the building through double doors and narrow corridor, the ‘auditorium’ space opens out into single void – 14metres long x 7 metres wide – with a picture window at the end, high white stucco walls and bamboo wood floors.

This ground floor area is unseen from the main arrival point. Instead, the visitor is drawn up the entrance stairs to the first floor piano nobile. The concrete roof over the landing has a narrow slit that separates it from the main body of the church, creating an informal porch. Entering the building through double doors and narrow corridor, the ‘auditorium’ space opens out into single void – 14metres long x 7 metres wide – with a picture window at the end, high white stucco walls and bamboo wood floors.

Daylight, as usual, has been a significant factor for Vector, with exquisite use of wall-washing most effectively from the curved overlapping roof that is angled to suit the highest point of the summer sun. Triangular creases in the western elevation allows the erstwhile altar crucifix to be suffused in sunlight.

Daylight, as usual, has been a significant factor for Vector, with exquisite use of wall-washing most effectively from the curved overlapping roof that is angled to suit the highest point of the summer sun. Triangular creases in the western elevation allows the erstwhile altar crucifix to be suffused in sunlight.

There are other tricks that the architect employs that are reminiscent of classic modern church design, from Ronchamp to Ando’s Church of the Light but effectively this building has its own a simple, rarefied atmosphere.

The main space is a bare, non-committal, non-denominational spiritual space with pews for 30 – 40 people. (The client’s wife is Christian and there are a small numbers of Christians in the local community). As a nod to the contemplative confessional, there is a single person meditation pod affixed to the north elevation into which people can presumably sneak during a service and simply gaze. A lookout, rather than an inward-looking space, the lectern has been placed off-centre to avoid blocking the view.

Nandaihe is being advertised as a tourist and recuperation resort, so maybe this church building is indeed the new genius loci after all. This is church as beach hut: a Crusoe-esque retreat for Beijing’s bourgeoisie to sample safely the long-forbidden religious experience. A chapel for the emerging well-being generation. With the pace of change happening all around them, Chinese people are understandably looking for a getaway from the turmoil of relentless rapid development. If that takes a romantic spiritual form, who am I to cast the first stone.

This article was first published in The Architectural Review

Detail: Beidaihe New District, China

Client: Beijing Rocfly Investment (Group) CO., LTD

Design Firm:Vector Architects

Principal Architect: Gong Dong

Project Architect: Dongping Sun

Site Architect: Dongping Sun

Design Team: Yi Chi Wang, Jiahe Zhang

Structural & MEP Engineering: Beijing Yanhuang International Architecture & Engineering Co.,Ltd.

Structural Consultant: Lixin Ji, Zhongyu Liu

Structure: Concrete Structure Material: White Stucco, Laminated Bamboo Slate, Glass Curtain Wall

Building Area: 270 m2

Design Period: 08/2014-11/2014

Construction Period: 11/2014-10/2015