A Chinese Utopia?

Review by Pierre Shaw [ Oct 2016]

Review by Pierre Shaw [ Oct 2016]

Shenzhen is the city of miraculous conception, born from nothing and yet emerging now as one of the planet’s most ferociously rapid urban developing city. From humble border town beginnings just 35 years ago, Shenzhen has thrown itself onto the world stage projecting its population from 300,000 to 12 – 15 million (no-one seems to know the exact figures). It is yet another step in China’s march to mobilise, urbanise and modernise.

Shenzhen is also home to URBANUS, an architectural firm that is getting agood name for itself within and without China. Its DenCity proposal is China’s entry to London’s first Design Biennale held at Somerset House which this year focuses on the theme of Utopia; a subject that has long captured the minds of authors over the centuries after Thomas More’s Utopia, first published in 1516. Designers and architects have only relatively recently added their contributions to the power and potential in imagining impossibly great and successful visions of a perfect society. The London Biennale provides the public a ticket for the latest soother to our contemporary anxieties about the future of mankind, reassuringly swept aside by some of the best designers in the world. If you have a ticket, keep hold of your receipt for now.

From Ledoux’s unfinished 1779 Royal Saltworks to 20th century Modernism’s Le Corbusier’s unbuilt 1925 Plan Voisin, architects have always had a complex and lasting relationship with utopia, ever seeking to envisage bold built forms as the city’s saviour.

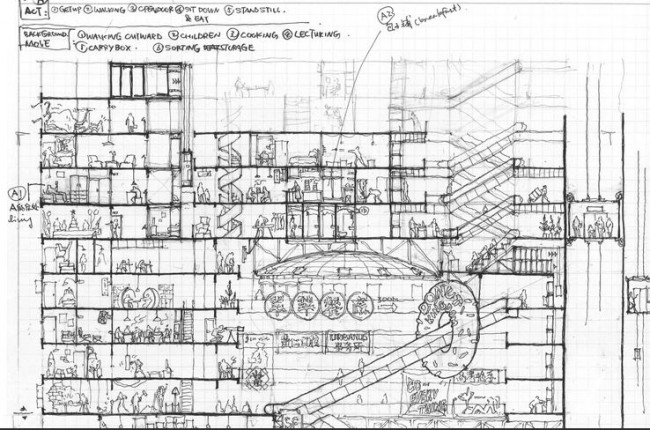

The attractively colourful and amusingly animated URBANUS project proposes an alternate, but distinctly modernist solution to Shenzhen’s consuming and expanding sprawl. Wipe the city clean and start again. This time around, create a dense high-rise island of megastructures that focus on affordable accommodation for the young workers working in its industries. Separated by kilometres of idyllic rainforest, each island would self-sustain its inhabitants using the imaginary future of green technologies. Each of the 30-5,000 residents would be able to move freely and easily through the block’s traffic-regulated interior.

The attractively colourful and amusingly animated URBANUS project proposes an alternate, but distinctly modernist solution to Shenzhen’s consuming and expanding sprawl. Wipe the city clean and start again. This time around, create a dense high-rise island of megastructures that focus on affordable accommodation for the young workers working in its industries. Separated by kilometres of idyllic rainforest, each island would self-sustain its inhabitants using the imaginary future of green technologies. Each of the 30-5,000 residents would be able to move freely and easily through the block’s traffic-regulated interior.

DenCity strongly evokes images of Kenzo Tange’s 1960 vision for Tokyo Bay in which communities of vast, floating super-structures interconnected across kilometres of open sea by a lace of high speed transportation links would provide an answer to Tokyo’s then rapidly urbanising population. Ron Herron’s 1964 Walking City proposed a world of massive moving bodies capable of supporting entire cities, cast off to wander the Earth’s abandoned surface. The idea of clearing a city and starting again isn’t uniquely modern but the tabula rasa or ‘blank slate’ was continually deployed, in theory and practice in post-war Europe, where an real tabula rasa of wartime destruction lay ready for restructuring; or where 1960s Space Age possibilities seemed to be a possibility.

And yet URBANUS’ modernist proposal, with very little to support their (utopian) annihilation of 36 years of Shenzhen’s city building, is at odds with its sponsors’ vision of Shenzhen’s neatly commodified and thriving as a ‘City of Design’. The Shenzhen City of Design Promotion Office publication is impressive. Reading it is like a bit like the moment from the imagined world of Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass when the Queen tells Alice she has believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.

The city’s development is truly impressive, nearly every statistic printed will tell you how Shenzhen is an outward-looking city that is open for business. A construction site for sheltering China’s capitalist interests. Branded and commodified for the globalised economy, the city is looking to emerging digital markets, new-generation information technologies and industries developing around innovation in biology and communications for an outward view of the world standing on it’s own platform. Shenzhen leads China’s cultural and creative industries making 175.7 billion yuan (UKP18 billion) in 2015, it leads the country’s venture capital institutions worth 300 billion yuan (UKP30 billion) in 2013, and now pioneers China’s pilot Free Trade Zone securing economic cooperation with its neighbour Hong Kong.

The city’s development is truly impressive, nearly every statistic printed will tell you how Shenzhen is an outward-looking city that is open for business. A construction site for sheltering China’s capitalist interests. Branded and commodified for the globalised economy, the city is looking to emerging digital markets, new-generation information technologies and industries developing around innovation in biology and communications for an outward view of the world standing on it’s own platform. Shenzhen leads China’s cultural and creative industries making 175.7 billion yuan (UKP18 billion) in 2015, it leads the country’s venture capital institutions worth 300 billion yuan (UKP30 billion) in 2013, and now pioneers China’s pilot Free Trade Zone securing economic cooperation with its neighbour Hong Kong.

So how does a utopian vision for south-east Asia’s most successful free market economy end up hitting “re-start” in DenCity?

Five hundred years ago, Thomas More wrote: “You wouldn’t abandon a ship in a storm just because you couldn’t control the winds.” URBANUS, in their words, are inspired by ‘past utopian thinking on cities’ seeking totalising built form as a typically bold ‘practical necessity’ to Shenzhen’s migrant workforce. Their answer to today’s globally connected world seems to be simply taken from another time. Whether Modernism’s solutions (during a very particular point in history) were successful or not we won’t discuss here, however we can say that we face completely new territory in our globalised and politically confused society with its own distinct complexities. Shenzhen’s own short history shows us that to believe that there can be one definitive solution to a constantly changing and evolving urban space would be naive and over-simplified. That, maybe, is the utopian project.