Prisoners of Cladding

One of the unintended consequences of the Grenfell tragedy is the threat of penury or bankruptcy for leaseholders across the country.

One of the unintended consequences of the Grenfell tragedy is the threat of penury or bankruptcy for leaseholders across the country.

by Austin Williams

It has been almost four years since the Grenfell Tower disaster, in which 72 people lost their lives in a catastrophic fire in a 24-storey block of flats in North Kensington, West London. The government inquiry into the disaster was set up in mid-2017 and its first findings released in October 2019. The second phase of the inquiry, hampered by the coronavirus lockdown, is still proceeding and is due to be concluded in late 2021.

The repercussions for the construction industry are, some might say, justifiably severe. Revelations of incompetence, chicanery, naivete, inexperience, and shoddy working practices at Grenfell has shone a light on common working practices across the construction sector. Fire barriers were omitted to save time and money, test results were fiddled or misunderstood, decisions were made by those unqualified to make them, materials swapped, shortcuts taken, blind eyes turned. Since then, fire safety has become a watchword.

The new Building Safety and Fire Safety Bills currently going through Parliament will seek to ensure that there are new tiers of local government responsibility and that residents, with first-hand knowledge of dangerous conditions in their blocks, will be “listened to”. The legislation has invented a title – the “Accountable Person”- who will have “to listen and respond to residents’ concerns and ensure their voices are heard”.

One group of residents that, until recently, has been completely ignored in the aftermath of Grenfell are the leaseholders in high-rise flats hundreds of miles away from Grenfell Tower, who just happen to live in apartment blocks clad with similar materials. Because of the focus of the Inquiry is on Aluminium Composite (ACM) cladding as a primary cause of the Grenfell disaster, other flats with similar cladding are being caught up in its wake.

In the initial panic, around 2000 buildings were identified. But instead of simply dealing with Grenfell-like high-rise buildings (which can legitimately be assessed as representing a risk worth addressing), the government pledged blanket remediation measured for buildings at 4-storyheight and over, in some instances, even second-storey flats with wooden balconies. As a result, 100,000 reasonably innocuous buildings and more than four million unsuspecting apartments came to be categorised as potentially dangerous. The major developer, Barratt has recently estimated that fixing the problems across all of its sites would cost £70m.

Immediately after the fire, the knee-jerk response was to strip the cladding off high-rise residential blocks across the country, and re-clad in ‘safer’ materials. But in many cases, remedial work was stopped halfway through when it dawned on developers that there was no clear source of funding. Half-stripped blocks – even less fire resistant and aesthetically unappealing – meant that these flats became immediately worthless on the market. The legislation calls for amongst other things, new sprinkler systems, door closer upgrades, evacuation plans, possibly additional staircases. The costs are staggering.

Replacing unsafe cladding on buildings may total £15 billion, nearly ten times the funds now available and it is estimated that 1.5 million flats are currently un-mortgageable, trapping around 3.6 million people in potentially dangerous, unsellable housing. It is rumored that the total costs cost may reach £20-40bn. The bill, at the moment, is being passed on to homeowners. With individual property bills ranging from £25k to £185k, leaseholders are being asked to stump up the cash for “essential works” or risk having their homes repossessed. (Admittedly, there is currently a Lords amendment advocating that leaseholders be banned from paying for such works).

The impact on ordinary people is financially devastating. One mortgage consultant explained that: “Risk-averse surveyors are reporting that they can’t be sure that a building is cladding free or fire safe, and as a result the mortgage company won’t lend unless they see the certificate, which the management company usually can’t or won’t provide.”(1) Financial adviser Martin Lewis describes existing leaseholders as “mortgage prisoners.”

The clamour is turning into a panic and is being driven by a demand for safety outside the bounds of common sense. While the legislation is going through Parliament, it is believed that these buildings are notionally at-risk of Grenfell happening again and so, while no remedial work is being carried out, local authorities have been employing Fire Wardens – men in hi-vis jackets – to wander around buildings looking for sparks. For this nonsensical activity, £12 million is being spent each month, in London alone. That’s around £3,600 per flat per month.(2) The bill passed on to residents with the bailiffs waiting in the wings.

So, what are the chances of a fire?

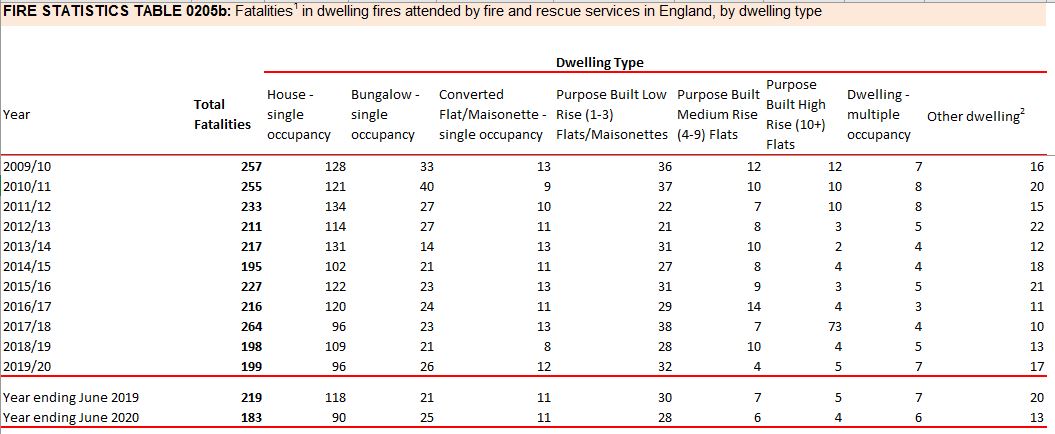

The most recent government Fire Safety statistics on domestic and residential fires shows that in high-rise flats, fatalities in England have been consistently low at around 2 – 4 for the five years prior to Grenfell and similarly remains low afterwards. The contrast with statistics on fire fatalities in houses of single occupancy, where regularly over 100 die each year, is stark. Non-fatal fire injuries total around 150 in high-rise buildings compared to 3000 in single occupancy accommodation.

Statistics for fires in high-rise buildings requiring the attendance of the fire brigade are reasonably consistent at 750-800 per year over ten years. The equivalent incidence of the fire service called out to domestic fires in houses of single occupancy is 16,500.

These stats have never caused a panic amongst occupants of single-occupancy houses of flats, nor should they. There are around 8.7 million homes of single occupancy in the UK, so the chances of a fire are 1: 500, and the chances of dying in a fire are 1:80,000. The government has tended to adopt the language of “zero-risk” and this kind of impossibly high-stakes risk-aversion has created an industry-wide safety zealotry beyond the bounds of what is reasonable, practicable or desirable.

The rise of risk aversion is in danger of destroying confidence in the construction sector and the high-rise housing market. Unsurprisingly, some leaseholders of so-called “at risk” apartments are also talking up the fire risk and demanding remedial action or more visible fire wardens, because they have no other way of appealing for help. Eliminating risk seems to be the only terms of the debate and the fact that this is an impossibility means that confusion and desperation is set to rumble on.

Actually, we should be talking down the risk! Leaseholders should be campaigning for freeholders and developers to put their apartments back together again – albeit to a high standard of materials and workmanship – because the law of averages demonstrates that these flats are not tragedies waiting to happen.

The chances of being involved in a fire are vanishingly small. Grenfell was a terrible tragedy, and in large part it was an accident compounded by a perfect storm of bad decisions and shameful inaction. Let’s hope that the specific plight of Grenfell survivors and their families are resolved to everyone’s satisfaction. But let’s not become paranoid about any building with cladding. That would be a second Grenfell tragedy.

——————————–

(1): Guardian: Thousands of UK flat owners can’t sell due to fire safety holdup.

(2): LBC: £12 million spent each month on fire warden patrols in London alone.

Tables: Fire.gov.uk