Driving Out Common Sense

by Austin Williams

by Austin Williams

The UK government has just announced new road safety measures that, they say, will save thousands of lives on the roads. Unsurprisingly, there is no timescale provided for this heroic life-saving initiative. But road safety has many components and assessing causality needs a little more subtlety than has been evident thus far.

Nowadays, a transport strategy doesn’t involve building any roads but is designed to reduce the number of people driving in the first place. Nudging people out of driving has been a guiding principle for transport planners and government ministers for many years. For them, accidents will be fewer because there are fewer people driving to have accidents in the first place. It also alleviates pressure on potholes… I mean the road space. And, of course, to double the whammy, they’ll be increasing fuel duty for those that persist in getting in their cars. As I found out recently, motoring is a slow, expensive business these days.

Over the Christmas holidays, I drove from north to south Wales and back. Laden with presents it seemed cheaper and easier than taking the train. After all, Transport for Wales have a regular supply of cancellation excuses: from a shortage of drivers, to delays on the line, or engineering works. So being one’s own driver usually offers a more reliable door-to-door service. It turned out however, that freedom of the open road wasn’t what it once was and not nearly as quick as I’d predicted.

On 17 September 2023, most 30mph speed limits in Wales changed to 20mph at a cost of £34.4million; with each new sign costing £1,045. Half a million speeding tickets were issued in 2024 alone in a furious bid to recoup the outlay. Advocates point out that during this period, fatalities on Welsh roads declined. But actually, they have been reducing steadily anyway, and road accidents in Wales had more than halved over the last 30 years. Curiously, there had been a slight rise during Covid, but since 2023, the trend of fewer deaths merely continued and cannot, in all good conscience, be attributed to the sluggish pace on the roads.

As it happens, most drivers fully respect 20mph speed limits where they intuitively feel that they are appropriate – outside schools at 3pm, for example. But of course, speed limiting signage and the ubiquitous monitoring cameras, are in place 24 hours a day, forcing motorists to inch past schools at 20mph even at 3 o’clock in the morning when no-one’s around. 3am is the hour of least traffic, pedestrians and accidents but we all crawl along as penance for having the audacity to drive a car.

At the end of 2024, Wales began re-setting most of its limits back to 30mph after hundreds of thousands of complaints. The announcement came from the ironically-named Senedd Transport Secretary, Ken Skates. The U-turn will cost the taxpayer a further £4milllon to get back to the status quo, with many people having lost their licenses in the meantime. At the moment, even though many roads are now re-designated to 30mph, some drivers in Wales are still being prosecuted for exceeding the previous 20mph limit because the signage hasn’t been changed yet.

This week, the UK Prime Minister announced new measures to impact car drivers across the country. For many people frustrated by Starmer’s latest announcements, there doesn’t seem to be much common sense applied to motoring policy.

Given that the government is pledging to reduce the number of people killed or injured on the roads, what is the reality of road accidents in this country?

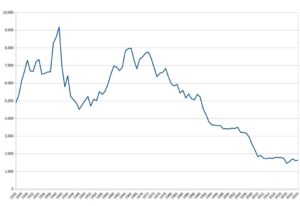

Fatalities on UK roads Graph by David X from various official sources

In 2025, the last year of record, there were 1,579 fatalities, a decline of 3% on the previous year, but still almost five people every day killed on the roads. To put that in perspective, if you are concerned about the dangers of outdoor life the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (RoSPA) records that 7,751 people died in accidents in the home. That’s five times as many as were killed in road accidents. What should be the response? Surely, if around 1,000 people died falling down the stairs then perhaps the government should mandate that we all live in bungalows.

One of the new policy announcement states that there should be a six-month gap between sitting a theory test and taking the practical driving test. This has been described as a sleight of hand by Seb Goldin of Red Driving Training (Times Radio, 7 Jan 2026) because it is simply putting a positive spin on the current 6-month backlog for driving tests. In other words, getting rid of the backlog by renaming it as a learning period.

Reducing alcohol limits to 50mg per 100ml of blood down from the current 80mg (20mg for new drivers) effectively means that any amount of alcohol consumption with result in a ban. The government has taken evidence from Scotland where drink-drive accidents fell in the first years of this policy introduction back in 2014 but seem not to have relied on the evidence once the numbers started to rise again. The number of fatal collisions is now 15% higher than in 2014. It seems somewhat fallacious to make the claim that this is a failsafe accident reduction strategy. The days when drivers commonly consumed vast quantities of lager and drove home are long gone. Just as wearing a seat belt is now mainstream, so moderation in alcohol consumption, or designated driver schemes are commonplace.

These new nudge policies on lowering permissible alcohol levels will soon be reducing trade for rural pubs. Already hit by national insurance hikes, business rates (scheduled for another government U-turn?) and rising prices, this could be the final straw for rural establishments. Lilian Greenwood MP, local transport minister, recently said that “We don’t want to stop people from going to the pub and having a great night out. What we’re just saying is don’t take your car. So that might mean … take a bus or a taxi.” Adding the price of a taxi to your 2 pints is quite a stealth tax. And, by the way, what rural bus service is she imagining?

Another element of the government’s proposals is that drivers over 70 will have to get their eyesight tested every three years. But, it says, they do not have to provide proof of this but falsely stating it will be a criminal offence. More importantly it seems unconcerned with the fact that the age group causing the least accidents in the UK are over-70-year-olds. Never mind, the end result will be fewer older people, especially those in rural areas, able to get around. I’ve nothing against eye-tests – especially when they are free for pensioners, and it seems like a fair requirement. It is also the case that the number of older drivers is rising rapidly, assuming a 16% increase in the number of people aged 70 from 2024 to 2032.

Drivers over-70 were involved in collisions resulting in 239 fatalities last year, where half of those fatalities were the drivers themselves. This begs the question: why is it, that when we speak of fatalities, we automatically assume that a) the death is that of an independent third party (a pedestrian or cyclist); and b) why is it automatically assumed that the driver is at fault?

In official government statistics, the contributory factors ascribed to most drivers involved in collisions is that they “failed to look properly”. But the same phrase is used as the most common factor for pedestrians involved in accidents and fatalities. 36% of pedestrians failed to look properly and 18% were “careless, reckless or in a hurry”. Furthermore, in the five years up to 2023, 1,872 fatalities were ascribed, in part, to “pedestrian impaired by alcohol”. In other words, drunk pedestrians standing or walking in the street late at night, struck by – let’s assume – an unsuspecting, sober and responsible driver. Maybe the walking and cycling lobby need “alcolocks” to prevent them swaying into the path of oncoming vehicles.

Tragic though these matters are, many of these tragedies have little or nothing to do with speed, with poor eyesight, with drink, or with wilful intent. That is why they are usually referred to as “accidents”. The consequence of Starmer’s new suite of transport restrictions will undoubtedly be indistinguishable from the historic trend of terminal decline in fatality numbers, down from their peak of 8,000 in 1966.

It would seem that the discussion needs to be a little more nuanced. While some of the government’s measures are reasonable, they are clearly missing the bigger picture.

With the rise of Motability schemes – of cars driven by 16-65 year olds with “illness, disability or mental health conditions” – we may soon find that there is an uncharacteristic uptick in the stats. Or maybe the decline in accidents and fatalities would have been greater if such a scheme hadn’t been introduced.

Similarly, while the government doesn’t collect ethnicity data at collision sites, a report in 2012 concluded that “14 per cent of all fatal road accidents in the (North Yorkshire) region were caused by Eastern European immigrants” and blamed it on their “cavalier attitude to drink driving”. Is this still an issue? Meanwhile, as many in the UK develop a cavalier attitude to the law, the Motor insurance Bureau points out that “there is an average of 300,000 uninsured vehicles on UK roads every day.”

It seems that there are more things to consider than worrying about pensioners’ eyesight. Before writing their policy documents, maybe it is Starmer who should’ve gone to Specsavers.

++++++++

Austin Williams is director of the Future Cities Project and series editor of “Five Critical Essays”.