White City Black City

Sharon Rotbard’s “White City Black City: Architecture and War in Tel Aviv and Jaffa” is much more than just an architectural history of Tel Aviv and Jaffa. The author, an Israeli architect and writer born in Tel Aviv, explores its development, and its sister city Jaffa through the lens of someone who has lived there continuously for decades. A critical examination of the accepted history of the region, “White City Black City” is also a strongly worded condemnation of the relationship between Tel Aviv and Jaffa. Sharon Rotbard has written a historiography of Tel Aviv’s Bauhaus world heritage site, deconstructing the myths of the city’s origins, showing the effect Tel Aviv had on Jaffa and the how the built environment can be used as a tool to wage war and achieve political aims.

The first English language edition of “White City Black City” could not have arrived at a more topical time. Britain, and its architectural community in particular, perhaps still holding on to some internalised guilt over its role in the creation of Israel and consequently the destruction of Jaffa, clamours so loudly to be pro-Palestine today that it sometimes sounds anti-Semitic in tone. After the recent July 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict, 20,000 people marched in the streets of London to protest Israel’s actions. Earlier that year only 10,000 people turned out to protest increased tuition fees and cuts to education; an issue happening on their own soil. The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) even passed a resolution in 2014 calling for the suspension of the Israeli Association of United Architects (IAUA) from the International Union of Architects until they ‘act to resist projects on illegally occupied land’.

Although originally written a decade ago in Hebrew, the author admits that he made no significant changes to the text. That this book still reads as completely relevant and not at all dated shows how intractable the problems of the region are. Although Tel Aviv and Jaffa have a unique story, their relationship can be read as a microcosm of Israel and Palestine in< “White City Black City”.

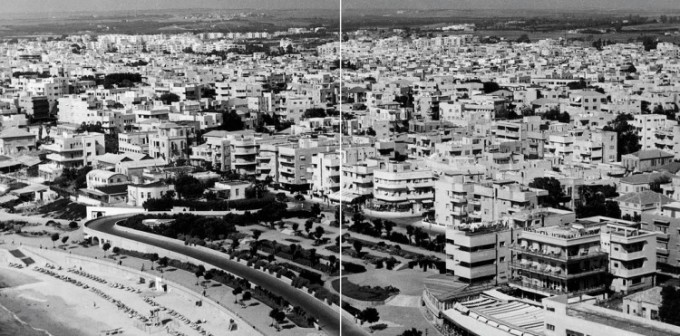

The book is divided into three parts, White City, Black City, and A Rainbow. The first part, White City, introduces Tel Aviv as a UNESCO World Heritage site, accepted by the academic and cultural community as a gem of both the Modern Movement and an unusually condensed example of the Bauhaus Style. The construction of a city, however, is not only physical but also cultural. A narrative must be created, and Tel Aviv’s story was told long before its actual birth. Taking us back to the earliest days of Zionism and the publication of Theodor Herzl’s novel “Altneuland”(old-new country) in 1902, Rotbard shows us how Tel Aviv’s history was written before it was ever built, and how the folktale of a Jewish homeland built on the dunes was recited until it was perceived to be true, despite the reality of the situation.

Rotbard calls this urban legend one of Tel Aviv’s “greatest deceits”. Unlike the local Palestinian sandstone constructions built directly on the region’s sandstone layer, Tel Aviv built its white city by first removing up to two meters of sandstone layer entirely, creating concrete foundations to replace the dunes. Although this criticism could be considered purely technical, Rotbard portrays it as a metaphor for Tel Aviv itself. Instead of building alongside the existing people of Jaffa using traditional methods and materials, Tel Aviv scraped away 4000 years of cultural heritage before constructing its White City. The main “urbicide” of Jaffa occurred in 1948 when at least 100,000 people, around 97% of the local population, fled the city as their homes were razed to the ground. The erasure of Jaffa’s original identity continued long after, as gradually all street names were changed and a completely new population moved in.

Rotbard calls this urban legend one of Tel Aviv’s “greatest deceits”. Unlike the local Palestinian sandstone constructions built directly on the region’s sandstone layer, Tel Aviv built its white city by first removing up to two meters of sandstone layer entirely, creating concrete foundations to replace the dunes. Although this criticism could be considered purely technical, Rotbard portrays it as a metaphor for Tel Aviv itself. Instead of building alongside the existing people of Jaffa using traditional methods and materials, Tel Aviv scraped away 4000 years of cultural heritage before constructing its White City. The main “urbicide” of Jaffa occurred in 1948 when at least 100,000 people, around 97% of the local population, fled the city as their homes were razed to the ground. The erasure of Jaffa’s original identity continued long after, as gradually all street names were changed and a completely new population moved in.

Rotbard is scornful of the legitimacy of the Bauhaus in Tel Aviv. Only four Bauhaus students ever emigrated to Palestine, and of those only Aryeh Sharon left a significant architectural legacy behind. Furthermore, the students of Bauhaus described it as more of an ethos and way of thinking than a coherent and identifiable style. Despite all this, Tel Aviv managed to turn Bauhaus into its brand, marketing the White City to the world as a marvel of Western European architecture and neglecting the historical and architectural heritage right under its feet.

The second part of the book, Black City, also delves into branding. If you believe Rotbard, everything Tel Aviv gained was at the expense of its sister city Jaffa. The epitome of this suggested zero sum game is the Jaffa orange. Once grown and exported by Palestine and seen as a symbol of national identity, the Jaffa orange was inherited by Israel after the mass evacuation of people from the city of Jaffa and its surrounding agricultural lands. Now Jaffa oranges are grown anywhere but Jaffa. By taking over key elements of Jaffa’s national identity, Tel Aviv effectively stripped away Jaffa’s narrative and exterminated the cultural construct of the city. This books argues effectively that architecture is a tool of war and oppression, and correctly wielded can influence culture, geography and history.

The final third of the book explores Modernism as a form of Western European colonialism. Tel Aviv is a city where colonialism won, and indeed never left. The occupiers are still controlling the land and its narrative from their defensive structures. Drawing on precedents who hold a condescending and at times downright racist attitude towards non-white non-Western-Europeans, Rotbard quotes Adolf Loos’s “Ornament and Crime”, shows Mies van de Rohe’s attempts to work with the Nazi regime and Le Corbusier’s cooperation with the colonial Vichy regime. Rotbard then implies that the attitudes of these founders of the International Style are similar to the attitude of Tel Aviv. Tel Aviv arguably strives to be white architecturally and metaphorically, wisely dressing itself in the Western-European Bauhaus style. Tel Aviv strives to be better, purer than neighbouring Jaffa, yet the means of achieving this whiteness corrupt the end result.

Rotbard tackles the complex history and image perception of a region steeped in myth and propaganda with ease. This beautifully translated publication is an excellent insight to the history of Tel Aviv and Jaffa, told through their architecture. A poetic account of a centuries-long struggle to cohabit, “White City Black City”sometimes feels too personal, recounting the grievous crimes against Jaffa that Tel Aviv has committed and demonising architecture by association. While the Romulan tale of Tel Aviv’s ascendancy and Jaffa’s demise may feel too personal at times, the description of Modernism solely as a Western-European colonial moment seems too general. Furthermore, Rotbard’s disdain of Tel Aviv’s inauthentic building methods and materials, stemming from the perception that the city ignored its immediate context in preference to a more general cultural movement, would come across more persuasively with some descriptions of pre-Tel Avivan local architecture. An incredibly thorough book, this is the only area where the reader might want for precedents.

“White City Black City” is not just an architectural history. It is a reflective and academic analysis of a region so steeped in myth and personal grievances that citizens from all over the world feel compelled to pick a side. “White City Black City” tries to see through the fog of subjectivism, and draws on the wider themes of architectural and historical authenticity, the role of marketing on an urban scale, and the creation (or destruction) of national identity through culture. These themes speak to us all in our rapidly shrinking but increasingly diverse world.