The Elite Power of the Greens

“One of my top priorities… is to champion global action for vulnerable countries on the frontline of climate change.” So said the COP26 President Designate speaking at the end of March 2021. Otherwise known as Alok Sharma, a chartered accountant previously employed as the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, this was the UK government’s latest pitch for environmental leadership.

“One of my top priorities… is to champion global action for vulnerable countries on the frontline of climate change.” So said the COP26 President Designate speaking at the end of March 2021. Otherwise known as Alok Sharma, a chartered accountant previously employed as the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, this was the UK government’s latest pitch for environmental leadership.

Unfortunately for the developing world, the “vulnerable” countries of which he speaks are poor sovereign states that have been screwed by supra-national bodies like the International Monetary Fund and World Bank for decades. They are about to get screwed again by the same people, but this time in the name of saving the planet.

From the 1980s, global institutions like the IMF have provided financial aid to heavily indebted developing countries on condition that they changed their economic policies, reduced inflation, devalued their currencies, etc. These early Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAP) imposed imperial-style diktats on the way that heavily-indebted countries were allowed to develop. They were forced to restrain internal demand, shift production to prioritize external markets and bolster policies that would provide a handsome return to the aid-giver.

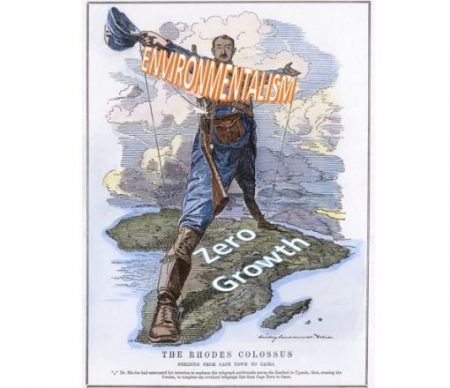

In recent years, global institutions no longer tell subservient nations how they should develop. Even though that sounds like a positive step in the right direction, unfortunately, nowadays the global leaders are nudging developing countries to consider whether they want to develop at all. All the signs are that the environmental movement is encouraging developing countries to stay where they are, undisturbed by anything as alien as economic progress.

In Western circles, the idea of “development” is regularly portrayed as a negative concept. Writing in OpenDemocracy, the authors of “’Development’ is colonialism in disguise” say: “The South emulates the North, captivated by its dazzling lifestyles in a seemingly unstoppable course that brings ever more social and environmental problems. Seven decades after the concept of “development” erupted on to the scene, the entire world is mired in “maldevelopment.” For these miserablists, it is a straightforward narrative which guiltily admits that the West has developed therefore we have to stop the developing world “making the same mistakes”. Not everyone can have the same level of development that we have in the West, they cry, because the carbon emissions alone would be ruinous. The authors do not reflect on the immiseration visited on undeveloped countries, nor do they recognise their own colonial mindset that denies development to the world’s poorest and voiceless (who, by the way, seem to want it).

The Agenda 21 process reprimanded those who didn’t get with the austerity programme, stating that “donors more often than not prioritized participation in so-called development-oriented projects and not sustainable development governance”. A focus on the environment, sustainable development and climate change are nowadays the primary concerns of donor agencies. The sovereignty and independence of the donee nation, their population’s needs and desires, are of little regard. As a consequence, environmental rhetoric and climate aid completely frustrate poor countries’ aspirations to develop. Essentially, the green agenda is inculcating a message of limits, of restraint, of caution, of moderation, and of compliance. More importantly, it preaches the sanctity of the environment and the destructive nature – rather than the social gains – of development. Humanity doesn’t get a look in.

The UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs is promoting the Green agenda on the basis that underdeveloped nations need to move beyond GDP as a measure of success if poor people are to be content in their penury. They are being encouraged to use the concept of “natural capital” to benchmark their developmental status. This means that a country’s decrepit infrastructure and low productivity can be balanced against the amount of forest cover and carbon sinks that it has. Hey, Malawi: You have no economy to speak of, but look at your magisterial coastline, unspoiled landscape, wildlife, and ecosystems. All of these must be factored into a nation’s economic accounts. In this way, the lunatic logic of environmentalism decides that the poorest non-developing countries are rich indeed.

In a BBC environmental programme about Bhutan, presenter Adedoyin Adepitan looks wistfully into the camera and says the country “has a different way of doing things. It is a way where economic growth and development isn’t everything. It’s not all about money. It’s about putting the environment and happiness at the forefront”. The Kingdom of Bhutan’s gross national happiness (GNH) index is a measure of “material and nonmaterial” aspects of an economy. Fortunately for Bhutan, its actual GDP has been around 7.5 percent for over forty years “making Bhutan one of the fastest growing economies in the world”.

For other less developed societies, happiness is in short supply but still the World Bank is pushing a Green Gross Domestic Product (GGDP) as a useful measure of economic growth with the environmental costs and services factored in. For example, a nation’s GGDP monetizes biodiversity and so encourages developing countries to become “stewards” of their environment rather than bespoiling it with factories, housing, industry, development. Bill Gates’ latest book, “How To Avoid A Climate Disaster” is explicit in advocating “paying countries to maintain their forests”. It sounds like a win-win for non-industrial societies but it’s merely a bribe so that they stand still in order to save the planet.

There are also indirect effects resulting from the fear-mongering reverberating around the climate crisis. Greta Thunberg tells the global media: “I want you to panic” and lo and behold, alarmist rhetoric about the overexploitation of water resources gains credence. When there’s a paranoia about a “global groundwater crisis” it seems common sense to insist that Sub-Saharan Africa stop exploiting its reserves. Indeed, there is huge pressure on the region to protect its water rather than use it. But it has been suggested that sub-Saharan acquifers will actually increase in capacity as global warming occurs, with “enormous untapped potential to catalyse development, underpin food security” and improve life chances. But because of the fear of depleting precious stocks of water, important and necessary infrastructure projects are difficult to fund. Thanks, Greta. Everyone is panicking. The “water crisis” hysteria means that the region struggles to develop and the vicious cycle continues.

Meanwhile, green-thinking is the new black. Most leading industrial economies are battling to be in the forefront of tackling the “climate crisis” whereby they can dictate terms of ecologically-responsible development to places like Malawi or sub-Saharan Africa. But as global tensions emerge between east and west, there is an unseemly battle royal breaking out between those who seek to control the environmental agenda.

The UK is preparing for the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow in November (even though it is unsure whether it is environmentally-responsible, or Covid-liable, to bring thousands of bureaucrats face-to-face). Less riddled with self-doubt, the EU is about to bring out a stringent package of revised climate and energy laws for a climate-neutral Europe by 2050. But US President Joe Biden has stolen a march on all of them by convening an online global Leaders’ Climate Summit on Earth Day on 22nd April where 40 nations will draw up plans for the future. In all these settings, which profess to set harmonious accords for the future, there are internal and internecine disputes about agenda-setting and the benefits that might accrue to political and business leaders of those in power.

China is biding its time over America’s faultering hegemony, but even it cannot evade the ethical power of climate change to bring countries into line. A Greenpeace activist in Beijing confirmed that “amid great geopolitical challenges… it is very important for the rest of the world to understand that at least on the issue of climate change the G2 are united again”. As far as the Western world is concerned, if climate change and pollution are the issues that can bring China to heel, imagine what it can do to impoverished countries with no power, no reserves, just trees.

_______________

Austin Williams is the author of the Academy of Ideas’ Letters on Liberty “Greens: The New Colonialists”.