Stay Home, Blame Cars, Save Lives

Pollution is problematic, but is it also overstated

by Austin Williams

When young Ella Kissi-Debrah died on 15 February 2013, the autopsy and subsequent coroner’s report determined that the cause of death was air pollution. This was the first time that air quality had been so explicitly stated. Because of that, Ella’s death has gone on to become a cause celebre, especially amongst anti-car and anti- pollution campaigners.

When young Ella Kissi-Debrah died on 15 February 2013, the autopsy and subsequent coroner’s report determined that the cause of death was air pollution. This was the first time that air quality had been so explicitly stated. Because of that, Ella’s death has gone on to become a cause celebre, especially amongst anti-car and anti- pollution campaigners.

Living just 25 metres from the South Circular Road in London, Ella’s short life was blighted by exhaust fumes from road traffic, and it is this that is now cited as the culprit. It has long been known that bad air is bad for you, but this ruling seemed to confirm the worst; that pollution kills. The original inquest actually stated that “there is no safe level for Particulate Matter.” With declarations like this, nowhere is safe from the poisonous miasma of urban life.

With clearer heads, we might suggest that people shouldn’t have to live next to major highways – not that cars should be banned. That air conditioning filters should be standard practice instead of having to seal stale air inside locked windows. And most importantly, that a young girl with severe respiratory failure would be to provide the best medical care, to invest in palliative care, and to give her short life the best experience possible.

A number of factors colour the outcome of the case. Firstly, Ella was a child with a severe, hypersecretory asthmatic condition causing episodes of respiratory and cardiac arrest and requiring frequent emergency hospital admissions. Her asthmatic attacks had already caused seizures resulting in 28 hospital admissions in as many months. In 2009, she was placed in a medically induced coma for three days when she was six-years old, for example.

Secondly, in a heavily politicised report by the coroner, it was documented that “failure to reduce the level of nitrogen dioxide to within the limits set by EU and domestic law which possibly contributed.” to her demise.[1] That same year, fewer than 1% of the urban population was exposed to concentrations above the EU annual limit values for PM2.5 and NO2.[2] in 2009. Ella, it seems, was in that unlucky 1%.

Mortality rates for children under five years old in the UK have improved greatly, from 142 deaths per 1,000 a century ago, to 20 deaths 50 years ago, to just 4 deaths per 1,000 today. That is still a figure of around 14,000 under-5-year-olds dying this year (admittedly Ella Kissi-Debrah died when she was 9 years old) but the improvements in child mortality are similarly impressive for later years. It is a rare event for a child to die in this country. A 2009 research paper on asthma deaths in the British Journal of Medical Practice (the year that Ella first showed signs of respiratory ill-health) states that “The standardised childhood death rate in the UK is 2.5 per 1,000. An average-sized (medical) practice with 10,000 patients including 1,500 children will have a child death about every 2 years.”

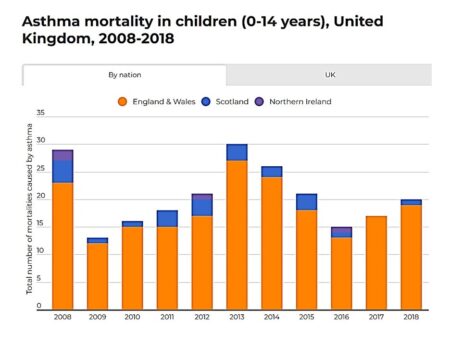

This low number may have been exacerbated by the main source of external nitrogen dioxide (NO2) i.e. road traffic fumes; while the main source of internal NO2 is caused by cigarettes or oil/gas heating/cooking appliances. This is one of the reasons that in India, for example, around 400,000 people die each year from the toxic fumes from breathing in the smoke from open stove fires in confined spaces. Back in the UK, The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health documents asthma deaths in the UK and states that “in 2017, 17 0–14-year-olds died in the UK.”[3]

The original certificate had stated that Ella’s death had been “caused by asthma” and yet the Deputy Coroner, Phillip Barlow who re-opened an investigation seven years later in 2020 added that pollution in the form of air quality was a “material contribution to Ella’s death”.[4] At the time of writing his report in 2021, the World Health Organisation had lowered its 2005 air quality guideline targets for particulates by 50%, and for NO2 by 25%[5] So his claim that air quality was not meeting standards may have had in mind the fact that regulations were being tightened at that time. At the time of Ella’s problems – between 2005 and 2013 – emissions of nitrogen oxides actually fell by 38% and particulate matter reduced by more than 16%[6] but this was not enough to meet the World Health Organisation’s future guidelines for 2021… but that is because those guidance figures – and they are guidance only – did not yet exist.

This case represented a shift from assuming that death might be caused by asthma, to a suggestion that asthma itself was triggered by a logically-prior issue that was external to the child’s genetics. Remember, the Deputy Coroner’s report comes at the height of the pandemic in which medical briefings regularly documented “dying with Covid” as opposed to “dying from Covid”, for example. This now shifted the dial. It was no longer sufficient to say that someone had “died from complications arising from asthma”; instead it became “dying with asthma from a polluted environment”.

In fact, asthma is hard to define. The NHS currently states that “The exact cause of asthma is unknown. Genetics, pollution and modern hygiene standards have been suggested as causes, but there’s not currently enough evidence to know if any of these do cause asthma.”

Whether car drivers can be blamed is up for discussion – and clearly clear skies and pollution-free air might help, but by the same token, the one group with the highest incidence of asthma and other breathing difficulties is cross-country skiers! These are fit, healthy people who spend their time in the cleanest of air. Clearly cold, dry air has a significant impact on asthma too.[7] Indeed, there are other factors that often dare not speak their name, like the quality of healthcare. On this point, The Royal College of Physicians has written that “46% of the children who died from asthma had received an inadequate standard of asthma care.”[8]

The graph is from the Office for National Statistics. 2019, Mortality statistics. It shows – somewhat arbitrarily – that the number of childhood asthma fatalities in 2009 were half that of the previous year. Admittedly, this could possibly demonstrate a link with traffic levels (in that congestion on Britain’s main roads and motorways fell by 12% due to the 2008-9 recession). As the cost of fuel skyrocketed, fewer journeys were made. But the reduction in drivers on the road at that time is nowhere near representative of the percentage decline in asthma deaths. Similarly, by 2013 (the year of Ella’s death) asthma fatality rates had returned to 2008 levels (30 per year), declining by 50% again in the following three years. This yo-yo effect is not explained – convincingly – by driving habits or even air quality mandates.

The main cause of Ella’s tragic death may have been her own morbidity – her severe asthmatic respiratory problems – admittedly exacerbated by her surroundings. Just as high pollen counts have adverse reactions for asthmatics, we tend to blame hay-fever, not the flowers. Indeed, the 2014 National Review of Asthma Deaths for the UK says that 15% of that year’s asthma deaths were exacerbated, in some way, by hay-fever.[9]

There is, it seems, an increasing tendency to examine forensically the minutiae of a case in order to find a way to apportion liability. We find it difficult to accept the reality of accidents. We are desperate to avoid the existence of tragedy. We increasingly find it difficult to cope with bad things happening and seem to need the catharsis of culpability. Heart failure, for instance, is often the biggest cause of death in the elderly in the UK, and yet those elderly people might have been exercising at the time. Ought we condemn Joe Wicks? Approximately 700 people in the UK die falling down the stairs. Should we only allow bungalows?

As it happens, in the last 30 years, we are living 5 years longer. In 1995, the average lifespan in the UK was 76 years, today it is 81. These improvements in the UK’s aging demographic have been caused by better medical care at both ends of life. Better elderly care has been supplemented by better survival rates for infants. In other words, the reduction in child mortality has boosted the mathematical average lifespan.

But when demographic modellers demonstrate that pollution reduces your allotted time on this earth, it is a) just a statistical projection and b) it refers to reducing, on average, “life expectancy by several months.”[10] Even if this were true, dying “several months” earlier than your predicted allotted timespan is small beer if we are living years longer anyway. All things considered, we are living longer, healthier lives regardless of air quality (which is also improving, year on year). It seems that one terrible consideration in all this is that poor Ella might simply have been a tragic statistic.

_______________________

Austin Williams

[1] Philp Barlow, Regulation 28: Report To Prevent Future Deaths. 2020. https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Ella-Kissi-Debrah-2021-0113-1.pdf

[2] European Environment Agency, Exceedance of air quality standards in Europe, 21 May 2024

[3] RCPCH, Asthma, The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2020 https://stateofchildhealth.rcpch.ac.uk/evidence/long-term-conditions/asthma/.

[4] BBC, Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah: Air pollution a factor in girl’s death, inquest finds, 16 December 2020

[5] World Health Organisation, What are the WHO Air quality guidelines? Improving health by reducing air pollution, WHO. 22 September 2021

[6] Defra, Improving air quality in the UK Tackling nitrogen dioxide in our towns and cities UK overview document December 2015

[7] Rikhard Mäki-Heikkilä et al, Asthma in Competitive Cross-Country Skiers: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis, Sports Med, 11 Sept 2020; 50 (11):1963–1981

[8] RCPCH, 2020, ibid

[9] Royal College of Physicians, Why asthma still kills The National Review of Asthma Deaths, Confidential Enquiry Report, May 2014

[10] Environment Agency, State of the environment: health, people and the environment, 26 January 2023

.