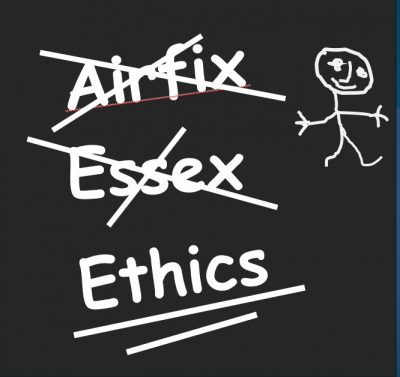

Five Critical Essays

by Alex Cameron

Five Critical Essays is a biannual publication that tackles a range of political issues through the prism of architecture and design. They have already explored issues around alleged bullying, discrimination, academic judgement, elitism, beauty and much else besides.

The short pamphlets are challenges to the profession – to re-open civic debate – on topics that many others worry about engaging with. As it says on the opening page, it has taken a leaf out of EP Thompson’s review of New Society, the 1960s cultural review magazine, that it aims to offer “hospitality to a dissenting view (as) evidence that the closure of our democratic traditions is not yet complete.”

The latest issue of the ‘Five Critical Essays’ series, ‘Five Critical Essays on

The latest issue of the ‘Five Critical Essays’ series, ‘Five Critical Essays on

Architectural Ethics‘ from the Future Cities Project (FCP) is a collection that speaks to the question of the ‘self-determination’ of the designer. The ‘five’ are by academics and professional practitioners, Dennis Hayes, Eleanor Jolliffe, Jide Ehizele, Alan Dunlop and James Woudhuysen, and are ‘topped-and-tailed’ by FCP director, Austin Williams and principal of Zaha Hadid Architects, Patrik Schumacher.

In his Foreword to the latest edition, Williams highlights the crux of the ‘ethical’ problem in design and architecture: ‘Ethics has stopped being a difficult philosophical tussle about how things should be. The intellectual battle about the various interpretations of the meaning of life have been ceded to compliance spreadsheets reliant on scientific, empirical or mechanistic evidence.’

This ‘intellectual battle’ has become constricted through its politicisation. In the hands of the design elites in the Academy, design associations and assorted design publications and commentary, ethics is being instrumentalised – used as a blunt weapon to whip the profession into shape – primarily around a social justice framework that includes (but is not limited to): sustainability, DEI, de-growth and the ‘circular economy’. [2]

Indeed, the ‘ethical designer’ is a monumental, politically motivated sleight of hand that is regulation-heavy and morally-lite.

But for the late, great Italian-American émigré, Massimo Vignelli, the question of an ethical approach, when applied to design, was straightforward and illuminating. It was a counterpunch to the design elite’s advocacy of the ideology of sustainability. In ‘The Vignelli Canon’ [3] he highlights the ethical question in design in what calls the three levels of the responsibility of the designer:

‘One – to ourselves, the integrity of the project and all its components.

Two – to the Client, to solve the problem in a way that is economically sound and efficient.

Three – to the public at large, the consumer, the user of the final design. On each one of these levels, we should be ready to commit ourselves to reach the most appropriate solution, the one that solves the problem without compromises for the benefit of everyone.

In the end, a design should stand by itself, without excuses, explanations, apologies. It should represent the fulfilment of a successful process in all its beauty.’

Today, among the elites in design, ‘One’, has been subverted, ‘Two’, has been recast and ‘Three’ is all but absent from the process. Today’s ethical designers have constructed a false distinction between ‘good’ clients and ‘bad’ clients (good being ‘ethically’ and ‘environmentally’ correct and bad being corporate or commercial). If clients or designers fail to live up to the prescribed sustainable goals of the design elite

or refuse to be cajoled into accepting the sustainability narrative and its regulations, they are shunned, shamed and ousted from polite society. [4] In turn, the public are only ever ‘used’ in a shameless pursuit of environmental evangelism – because the design elites know what is good for them!

Vignelli’s approach was that of the independent designer, free from ideological and political constraint. It asserted the role and function of the designer as a mediator and transmitter of ideas, in the service of the client and the public.

An ethical approach to professional practice is crucial. But it must be free of ideological constraints and political activism. The opening essay by Dennis Hayes implores us to ‘take ethics seriously’. A more grown-up discussion is certainly required if design is to regain a sense of its transformative potential. Five Critical Essays on Architectural Ethics is a vital start in the process.

This article first appeared on the Academy of Ideas Substack

Reference:

[1] http://futurecities.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Ethics.pdf

[2] https://www.architectsdeclare.com/

[3]

https://www.rit.edu/vignellicenter/sites/rit.edu.vignellicenter/files/documents/The%20Vignelli%20Canon.pdf

[4] Bauman, I. (2022) A truly ethical architect would have turned down a World Cup stadium, The Architects’ Journal, 16 November

Alex Cameron is a graphic designer and a design and cultural critic. He is the publisher of RePub, a curated digital journal of previously published writing on design. He is a member the editorial board of the Scottish Union for Education